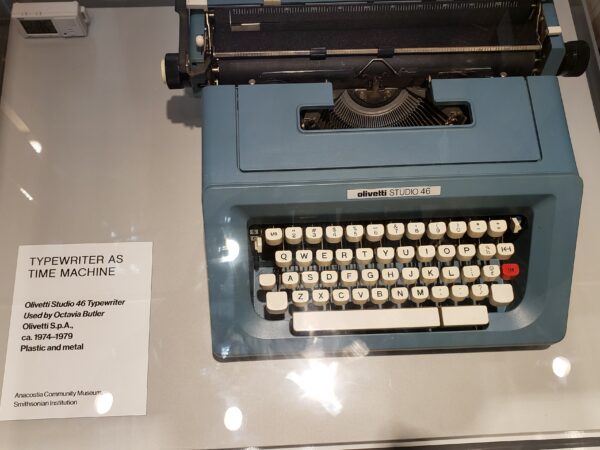

As literary works of speculative fiction, Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower (1993) and Parable of the Talents (1998) thrust us into an all-too-near future, offering a haunting perspective on what our world could entail by the year 2035. In 2024, however, Butler’s Parables are no longer mere imaginative forays into the future.

“I am the sum total of a thousand years of misery and striving! You may have given us this broken immortality, but I will be the first to die without fear!”

“Your clay is the clay of some Litvak shtetl, your air is the air of the steppes.”

“I was only imagining it. Being freed.”

Taubes’s novel continuously asks how we distinguish—if we can—between dreams, life, and books. Who or what speaks to the one who dreams? To the reader of a novel? Are dreams and novels and other kinds of books various mediums through which the dead speak? Can we hold this to be true while still honoring the dead as dead?

How does literature shape the world, and the bodies, social forms, and political acts that constitute it? What particular roles might the category of religion, and specifically religious experiences, play in such shaping?