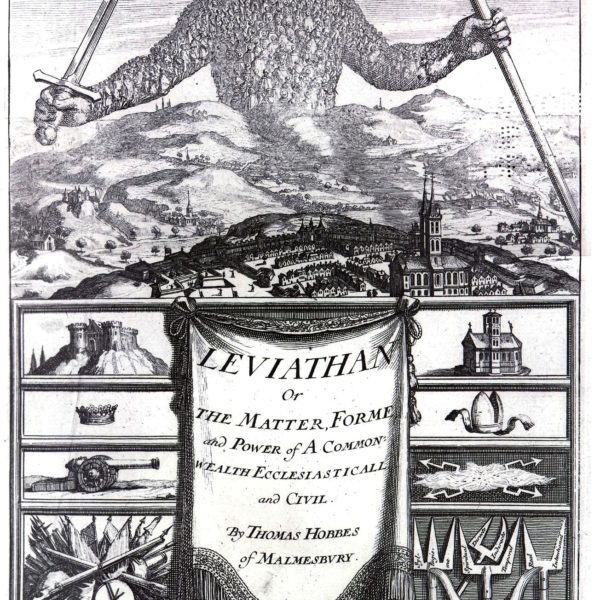

Christian political witness must be built around and declare Christ as the great eschatological stone laid by God. He must either be approached as the stubborn obstacle, arresting the development of all idolatrous political visions, or as the chief cornerstone, the sure and solid basis from all else can take its bearings.

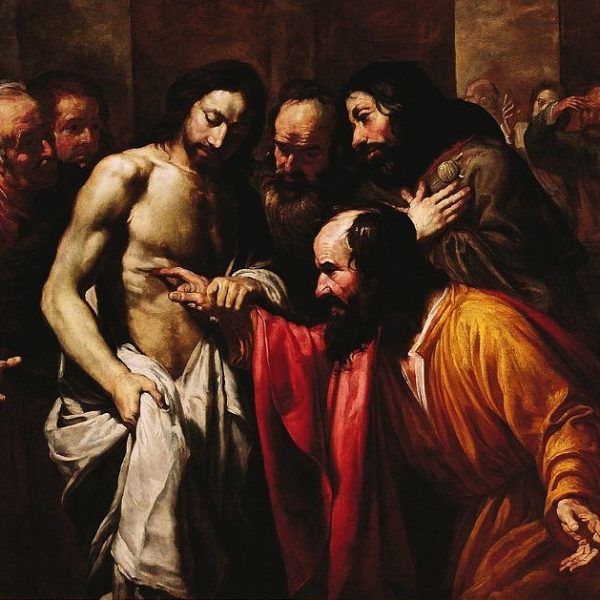

Real faith knows and embraces doubt and questioning. Rather than locking ourselves in, as the disciples first did, we should learn from the curiosity of Thomas. The opposite of faith is not doubt but fear, and it is time to shed our fears.

By Fritz Wendt