Following Bush’s consecutive victories in 2000 and 2004 the Christian right have been labeled the ‘backbone’ and ‘base’ behind the Republican Party’s electoral successes.[1] Evangelical born-again Christians constitute around 26% of the US electorate according the latest Pew Research poll, of whom three-quarters consistently vote Republican.[2] For forty years the considerable convening power of these faithful conservatives have made them an attractive constituency for Republicans to court. Aligning with their social and cultural concerns, this relationship has generated a distinguishing feature amongst Western politics, the American ‘values voter’.

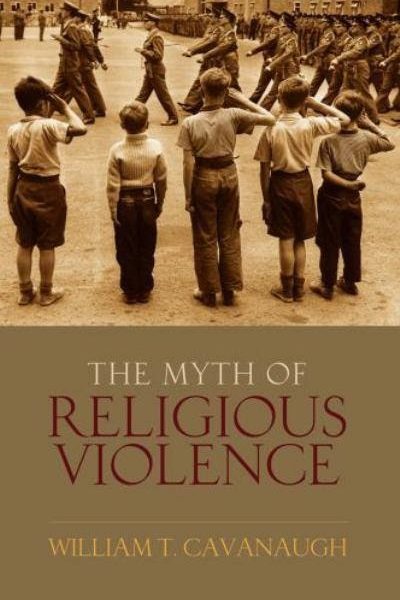

Issue 15.6 of the journal Political Theology is a special issue on William T. Cavanaugh’s The Myth of Religious Violence. Dr. James Murphy served as guest editor of the issue. Below he introduces the symposium.

The appearance of William Cavanaugh’s important new book offers a strikingly new take on the familiar debate about religion and violence. According to Cavanaugh, it has become a very widespread article of faith that there is something especially dangerous about religion.

The 2015 Balkan Summer School on Religion and Public Life (BSSRPL) will be devoted to the theme Conversion and the Boundaries of Community. As with previous schools, it proceeds from the idea that religion and other forms of collective belonging are central for the life of both individuals and society, and that our religious communities are often those to which we devote our greatest loyalties.

The Apostle Peter calls for the virtues of patience and peace in our waiting for the eschaton. At face value, these virtues might appear more congruent with an apolitical complacency. However, closer reflection reveals that they involve both the work of bringing peace and commitment to works of anticipation.

Justice fails where civil law and order are privileged over peoples’ ability to determine their destiny by confronting affronts to their dignity by legitimate powers. Let me offer two examples. I confess I am still in love with the Occupy Movement (OWS).

One can read the results of the 2014 mid-term elections in the United States in terms of whatever dominant political inkblot they favor. The narrative of the American right-wing, of course, is that the resounding Republican victories at both the Congressional and gubernatorial levels constituted a resounding repudiation by the voters of the Obama administration’s policies and pari passu the much vaunted progressivist politics that seemed to have finally taken solid root in American political soil with the 2008 election.