Jesus doesn’t ban sitting or reclining in public. He encourages it, supports it, and even participates in it.

Paying attention to Herod’s fears about Jesus can keep us from depoliticizing the gospel.

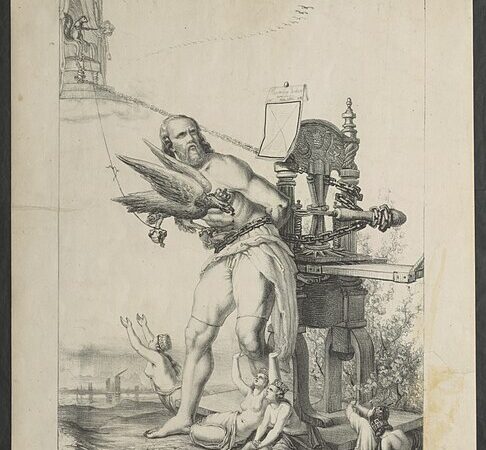

For Marx, religion is more than “the opium of the people,” it is the mirror of society turned upside down. This essay examines Marx’s critique of religion as well as his critique of other contemporary critiques of religion. This critique of religion became the starting point of his critique of political theology and, later, political economy.

In what follows I want to trace a political theology of miracles that makes possible their circulation in U.S. revivalism. A straightforward theology—namely that God does miracles—is certainly part of the motivating belief for revivalism. But I want to trace here the political contours of revivalisms’ continuous circulation of the miraculous, well past the time that secularization theory suggested that they would give way instead to secularity, science and the enlightenment.

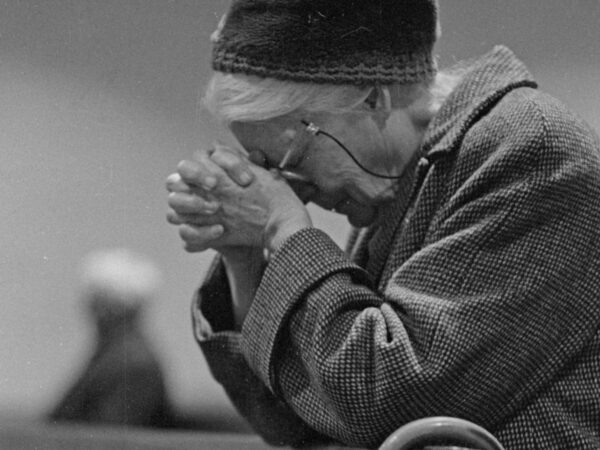

The messianic banquet imagined by the Jewish sages nurtures attitudes of respect, blessing, recognition, and wonder. These comportments converge in humility, an earthbound ethic that we practice together, through speech, action, and the work of dwelling.