In my book, The Right of the Protestant Left (Palgrave, 2012), I tried to restore Niebuhr to his precarious place within what I called the “old ecumenical Protestant left.” The reality is, the more Niebuhr’s celebrity rose among those outside of the church, the more marginal I found that he became to the main currents of liberal American Protestantism. I’m not referring here to the pacifist circles that Niebuhr turned his prophetic pen on. Rather, his friends, colleagues, and younger brother were so frustrated by Niebuhr’s indifference toward building a inter-Protestant world community—their chief interest—that they even considered leaving him out of their project altogether. Niebuhr was eventually reconciled to the ecumenical movement by his critique of “secularism” and his analyses of national and world problems through the lens of “original sin.” Still, those closest to Niebuhr continued to deride him as the “sackcloth and ashes man,” the “sin-snooping” saint who was fundamentally out of touch with the Christian hope….

If it is at all possible, a Muslim hopes to live in a society where Islamic norms, morality and etiquette flourish, and where they cannot be publicly violated. Similarly, if it is at all possible, provided that he does not perpetuate further harm, every Muslim should command the right and forbid the wrong.

This is the first time that I’m posting to the Political Theology blog, and I’m risking a re-post, no less! But I thought readers of this blog might be interested in some of the conversation that’s unfolding at An und für sich this week. Brandy Daniels has been posting some reflections on gender in the theological academy, and Anthony Paul Smith has posted something on ontology. I’m bringing these two things together, you might say, in a brief reflection on gender & ontology. I’m asking, in essence…

The recent interest shown in religion and, specifically, Christianity, by otherwise non-religious thinkers has been something of a boon for theologians and the like-minded. Even when such non-Christian appropriations of theology offer a presentation of Christianity radically different from received orthodoxy, the very fact that the effort has been made is often taken as a signal of the continuing preeminence of a largely traditional Christian thought and practice. As Paul J. Griffiths has suggested, such thinkers, left without any other viable critical options, are “yearning for [the] Christian intellectual gold” that the church has always held in reserve. Because of this, their services can easily be enlisted for theology, since, as John Milbank has often suggested, it is theology alone that offers any real alternative.

Such readings of this so-called post-secular “turn to religion,” however, tend to move too quickly to theology, and this is especially the case with Agamben. Although some may wonder if Agamben’s putative appreciation of theology means that he is in fact a Christian, his various forays into theology—notably, The Time that Remains and, more recently, The Kingdom and the Glory—present, I suggest, a much different picture. Specifically, among other things Agamben’s reading of the theological tradition represents a concerted effort to profane that tradition, to render it inoperative for a new use, a use that I characterize as non-non-theological or non-non-Christian….

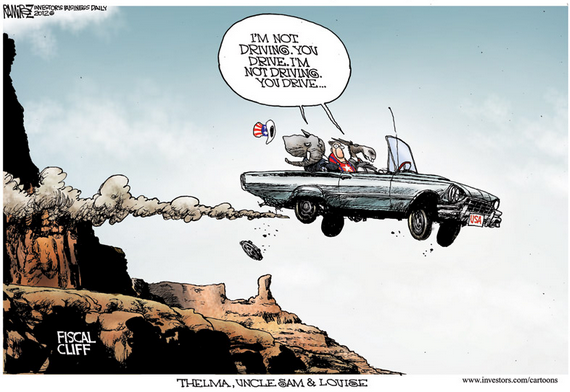

It is a challenge to reflect on politics and advent together. As advent emerges and we begin to anticipate the emergence of God’s presence into the world anew, as we expect the child who taught peace and preached liberation for the poor and oppressed, I cast my eyes on the political landscape and struggle to glimpse what might be breaking forth with new life. Perhaps this is a problem with how we conceptualize the birth of Jesus, as a grand cosmic event, an episode of a preordained salvation history, the inauguration of a new kingdom of peace on earth. There is another element to this extraordinary story, its ordinariness. Jesus is born in a Galilean backwater, to an unwed teen mother, lost in a crowd of travelers. Jeremiah prophesied to his ancient community about a time when justice and righteousness will emerge into history. We still await the fulfillment of this prophesy. But refracting this vision through the circumstances of Jesus’ birth will perhaps teach us to look for this hope in unexpected places…

In the 17th century, although the evangelical theme of the two kingdoms is everywhere. It is often somewhat hidden, though operant, behind other more forefront matters of contest–self-interest vs sociality as the basis of society, the divine or human grounds of legitimate rule, the relation of the State to nascent civil society, public and private–and sometimes the thing itself goes under aliases. It sometimes plays a greater role in the thought of the doctrinally idiosyncratic, for instance Hobbes, than it does in that of those otherwise more orthodox, such as Richard Baxter. This is a very vast and complicated field. Given that this is to be such a short overview, we will consider here merely one aspect of Lutheran two-kingdoms doctrine, that of the denial of political power to the clergy, and point to a few landmark instances…