Since the risen Christ embodies the gift of hope for those who follow the post-resurrection Christ, our reading of the Johannine narrative on the encounter between the risen Christ and the followers ought to open our hearts to encountering difference as an opportunity to replicate the gift that the followers received – openness to difference as the means by which God chooses to make God present in our world.

Jesus’ claim to be the good shepherd is much more than a comforting metaphor. It is a claim to kingship and a clarion call to surrender our wills and follow him to green pastures. His kingship subverts hierarchies. He models followership for us and ushers us into wide-open spaces where we can flourish in his upside-down kingdom.

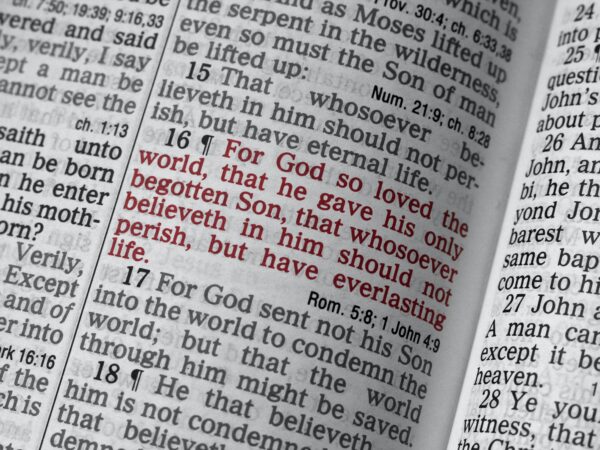

Following Jesus the Dao in flesh is to follow the way of liberative freedom, a freedom to embrace the openness of Jesus’s multifaceted witness instead of reductively boxing him in by way of the Logic of the One.

Jesus’s followers seek a “prophet” who serves human desires for control and vengeance: the power his followers think is essential in order to defeat their human oppressors. They forget that the prophet only ever serves the Divine will, which has a vision wider than the cosmos, concerned with re-establishing the harmony that was written into the fabric of creation from its very beginning.

In our times when critical thought is suspect and even scientific facts have become articles of faith in need of defense, to play the double bind between the ethical and the political is the constant task Christians and others must continually engage in. This play contains serious risks, no doubt. What gives grace its generosity and generative capaciousness also makes it liable to be the locus of opportunism and oppression.