For decades now, we seem to have been living in “end”: the end of history, the end of ideology, the end of theory. Parties nominally of the left (“New Labour”, “Wall St Democrats”) joined those of the right to enforce “democracy” abroad and a “third way” of free market reliance at home. Ideologues and theorists had ceded decision-making to technocrats, and no one need worry about such esoteric matters as justice or fairness, since all we had to do was sit back and let a properly-tuned market deliver optimal outcomes to everybody.

This book emerged from my attempt to understand what is going on when Deleuze’s philosophy speaks about creation. Along these lines, “Deleuze and creation” names the problematic that consistently runs throughout the book, even as addressing this problematic requires working within the distinct registers of the philosophical, the theological, and the political.

Isaiah offers us a startling vision of a society beyond scarcity and gross inequalities of wealth, leading to a subversion of all our economic logic. If we are prepared to re-conceive our world as a divine gift to all, we will be prepared to work towards a day when no one is excluded from God’s bounty.

The “postmodern condition,” as Jean-François Lyotard designated it in 1979, is an “incredulity toward metanarratives.” That definition has been recited interminably by those grasping for a familiar sound-byte to encapsulate the significance of postmodernity. In the last few decades it has acquired overtones of a playful cultural experimentalism that has somehow outgrown the need for authoritative accounts of the meaning and purpose of human history.

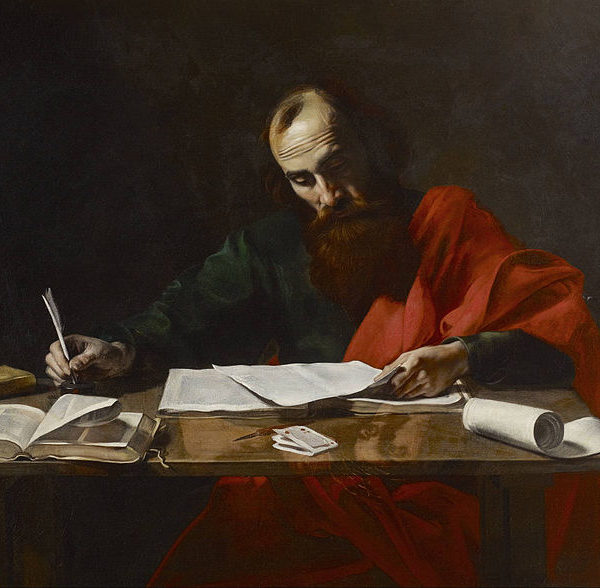

Paul speaks to our self-conscious understanding of tragic fatedness in Romans 7. Like him we long to be released from such an apparent fate, where we are not free to live as we know we could and should. This is more than an individual bondage to sin. It recognizes that sometimes we are prevented from living as we feel we ought by more than our own will; sometimes we are oppressed by the wills of others or even a system which seems to have a will of its own that is impermeable to reason.

The attack of The Islamic State of Iraq and al Sham (ISIS) on Mossul and its march on Baghdad has taken the international community by surprise and raised the possibility of another US intervention in Iraq, with the hope it could prevent the downfall of the country into a sectarian war. Such a scenario is highly improbable because of the nature of the Iraq crisis that is first and foremost political and not religious.

. . . Pastors and church-leaders for the past two years have been very vocal in their efforts to ‘welcome the stranger’ through immigration reform and in so doing are reframing evangelical Christian concerns beyond the rote of life-issues. . . . Though evangelical leaders have pushed for reform, this hasn’t yet filtered down to evangelical congregations who are amongst the most skeptical of CIR. The Public Religion Research Institute (PRRI) noted in 2013 that white evangelical Protestants were the least likely of all religious groups to support a path to citizenship for illegal migrants.