The purpose of this book is the clarification of the American mind, especially Evangelicals [….]

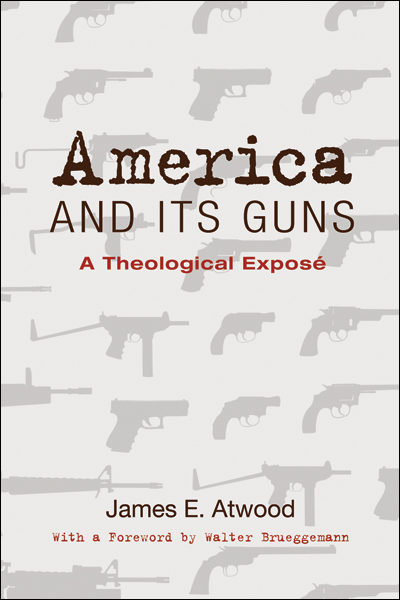

As the golden calf gave the ancients a false sense of security, many twenty-first century Americans look for security in weapons. When our leaders are absent or fail us; when our God is invisible and from all appearances is absent from our lives; when we don’t know how we can keep going; when we are consumed by our fears and feel threatened by those who are not like us, those are the moments when new idols are imagined and fashioned and desperate people give them their ultimate concerns, devotion, and focused attention.

The Royal Remains is a culmination of years of reflection on the conditions of the emergence of modernity, the ways in which it has been underpinned by a pound of ‘spectral yet visceral’ flesh. The book presents a complex politico-theological and psychoanalytic narrative about how the demise of transcendence has left us with a ‘surplus of immanence,’ a bodily too-muchness, an errant fleshy excess that still defines our condition and haunts it. From Marat’s death to Rilke’s Malte, from Kafka’s “Country Doctor” to Foucault’s biopolitical body, I track the palpitations of this surplus and explore the possibilities of developing new ways of living with and through it.

“The Practice of Prophetic Imagination” (Fortress, 2011).

This new book is for me a continuation of my earlier book, The Prophetic Imagination (Fortress, 1978). It is an attempt to think about “prophetic preaching” in the context of the US church where any prophetic dimension to evangelical faith is mostly unwelcome.

I have wanted at the outset to correct two most unfortunate caricatures of the prophetic. On the one hand, there is a conservative tradition that thinks that the prophets are primarily in the business of “predicting Christ.” Of course there is no such thing in this context. On the other hand, liberals regularly associate “the prophetic” with social justice and social action. But it strikes me how rarely the ancient prophets take up any specific issue of social justice.

We began work on this Reader with the realization that there was no recent collection of readings in contemporary political theology. Our moment is complex and difficult to come to grips with. It is characterized by God refusing to go away, with people of numerous faiths not taking the much-touted, purely secular politics lying down. Whether one sees this as a recent development (post-9/11, say) or the way things have always been depends largely on one’s perspective. Do the most pressing questions have to do with Christian theology’s inherent and ineradicable relevance to all things political (human well-being, the nature of power, and so on)? Or do they have to do with the reverse—the fundamentally theological nature of politics, even where religious questions have been thought most successfully to have been purged from it? It will take more than a reader to answer such questions, but collecting a wide variety of voices in one place can help us understand why we are now faced with them.