From the perspective of political theology, the presence of Indigenous peoples and settlers shaped by historical and ongoing settler colonial relations raises important political and religious questions about the possibilities and conditions of sovereign Indigenous existence and the (im)possibities and conditions of restorative or reconciled settler futures.

Refusal is a strong current resisting the structure of settler colonialism. It crashes, churns, and erodes the death-dealing dams of settler knowing. Its path turns away from the settler’s gaze.

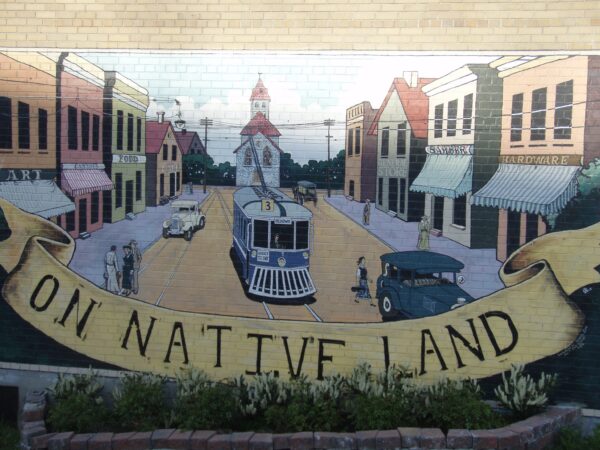

Chen suggests that Western political theologians should incorporate more resources from local knowledge—such as popular culture, literature, films, and music—in order to notice resistance in daily life.

The Gospel of Mark’s beguiling beginning bids us to consider the dangers of beginnings. John the Baptist’s heralding of Jesus’s coming was not the finality of salvation, but merely a herald to its coming. In this light should we consider our works of bringing God’s salvation and liberation to the world. The work of justice and liberation is long and hard, and many of us will be called to herald it, to lay the groundwork for its eventual manifestation.

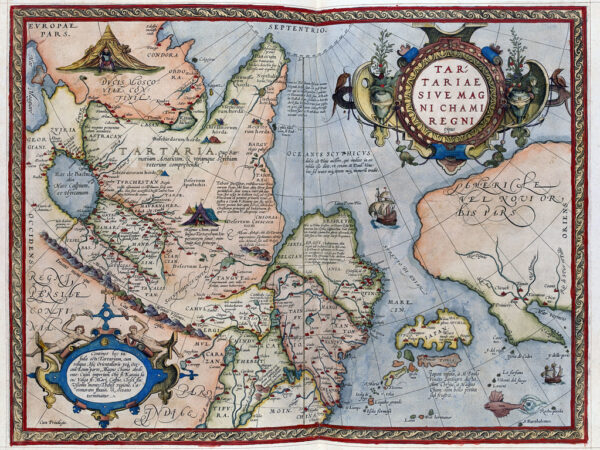

Is it the case that the European political theology is indeed derived, not from the universal requirements of any sovereign order (as Schmitt sometimes claimed), but rather from specific Christian underpinnings? Or is it the case that a fundamentally similar political ideology, one which depends on the logic of sovereignty rather than on parochial cultural assumptions, can indeed be found elsewhere?

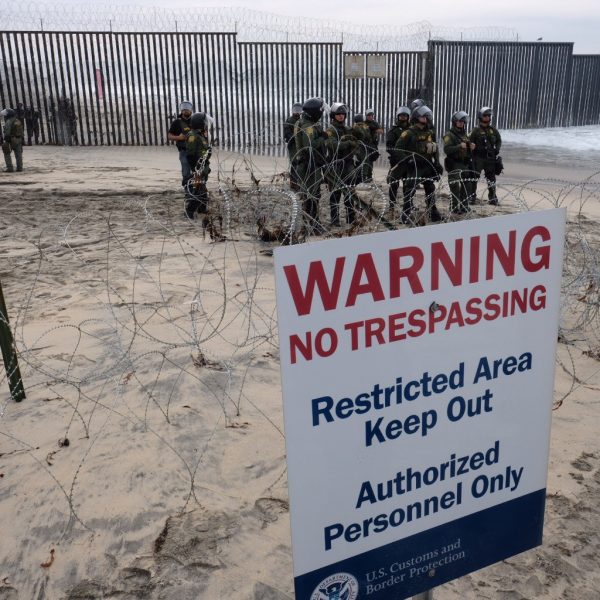

Borders signify the advancing presence of imperial desires and colonial fantasies of gradual yet total dispossession and disappearance of peoples of other nations that continue the founding settler colonial violence in the US.