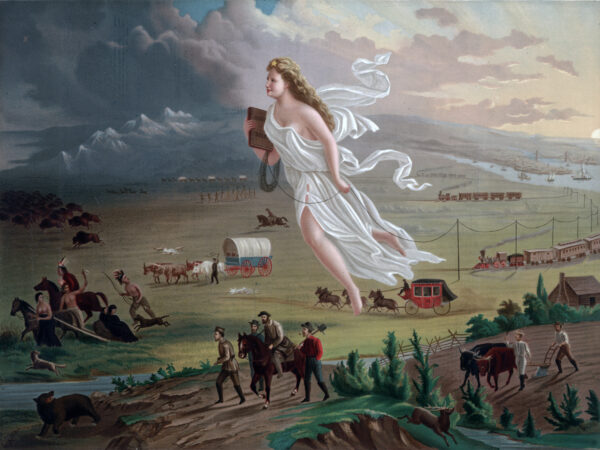

There’s an understandable temptation to think that climate disaster is nature’s way of rebelling against the Anthropocene. But this is a dangerous way of thinking we should ward against.

Judith Butler’s work in queer theory inspires Catholics to consider the material relations of the body and contributes to a mystical-political, eschatological hope.

Jesus’ saying about the destruction of the temple gives us a way to view human structures as the powers they are but also as provisional—as all human things are.

Panic leads us into the fruit of the flesh rather than living out the fruit of the Spirit. It distorts the Christian message and often leaves us like burning husks on the side of the road.

As it is often detached from its broader context and treated as a standalone paean to love, the significance of 1 Corinthians 13 within Paul’s overarching argument about the Church as a polity is often neglected. When the context of this chapter is appreciated once more, its political significance will emerge.

As a PhD student just starting my dissertation research I happened to meet the department chair of the theology department at a major Catholic university (my interlocutor and his university will remain anonymous). When he asked about my dissertation, I told him that I was researching Henri de Lubac. In a condescending voice he replied, “I didn’t realize anyone was still studying him.” I sheepishly responded, “Well, yes. Yes they are.”