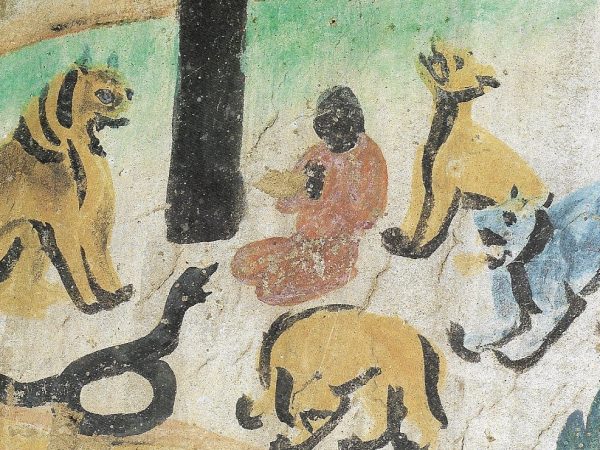

These books demonstrate that animal studies as a new field offers a powerful perspective for understanding the history shared with our companions in the multi-species universe.

This article demonstrates how the living memories of Malabar rebellion evade the logic of the historical narrative. The native memory of the rebellion appears to have subverted the neatly drawn schemes such as ‘Hindu’ vs ‘Muslim’, ‘cruelty’ vs ‘compassion’, and ‘horror’ vs ‘fascination’ etc. that animate the logic of historical writing.

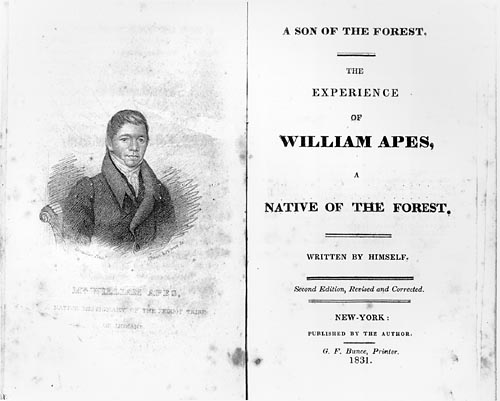

William Apess, like Walter Benjamin a century later, sought to shift the paradigms of society with history and theology as orienting poles for colonial critique. Anticipating Benjamin, Apess looked to those who had been wrecked by the advance of colonialism as the grounding site for historical and political theological inquiry.

The judgment of history is a moral belief that, somehow in the long run, the good and the true will win out, since the “long arc of the universe bends towards justice.”

Joan Wallach Scott’s On the Judgment of History serves as an invitation to uncover a multiplicity of traditions, perspectives, and forms of agency that embrace discontinuity and tension while resisting closure, and the essays in this symposium function as an active experiment in precisely this type of endeavor.

Could prophetic politics, with its unique emphases, allow us to envision another, possibly less dogmatic and more differentiated form of political theology? Could focusing on the schism between prophetic voice and political institutions reveal a different understanding of political theological concepts, beyond the realm of power and sovereignty?

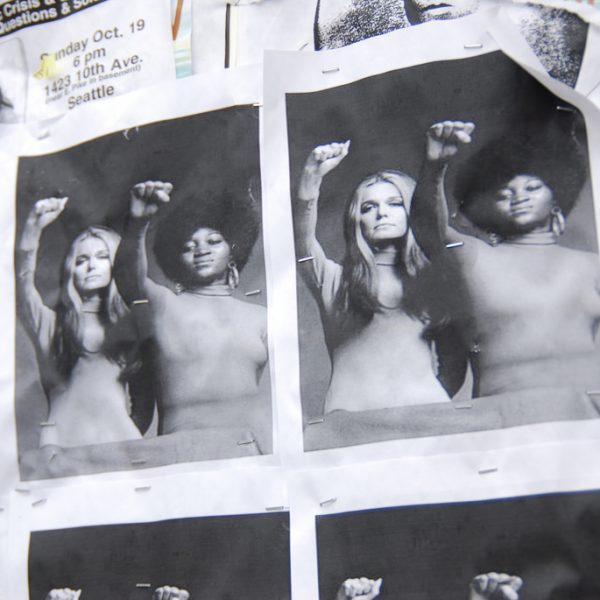

Why has political theology been so resistant to addressing questions of sex, gender, and sexuality in any serious way? Are there any intersections between queer feminist criticism and political theology, and what would it look like if the two methods were brought together?