I have been writing about torture for the last decade. Does the recently released summary of the Senate report reveal anything that requires reconsideration of my earlier work? Surely, it is not news that the Bush administration, particularly in the first term, pursued a practice of torture. Nor is it news that the practice was not successful. After all, the turn to torture was puzzling partly because we have long known that it is not an effective means of obtaining information. In fact, torture is best understood as a practice not of inquiry but of communication.

One can read the results of the 2014 mid-term elections in the United States in terms of whatever dominant political inkblot they favor. The narrative of the American right-wing, of course, is that the resounding Republican victories at both the Congressional and gubernatorial levels constituted a resounding repudiation by the voters of the Obama administration’s policies and pari passu the much vaunted progressivist politics that seemed to have finally taken solid root in American political soil with the 2008 election.

In the Passover we find a myth of the foundation of a nation that differs markedly from the contractarian myths of the Western liberal tradition. It disclosure of the sacrificial basis of the political order offers us a hermeneutical key for understanding the roots of our own nations and helps us to understand how we might be established as communities of faithful witness to them.

The activity of religious proselytizing or evangelism is often under attack, and would seem to be increasingly so today. Sometimes critics suggest that most proselytizing is immoral, while at other times they call into question the very institution of proselytizing. In other words, proselytizing is considered to be immoral by its very nature. This opposition to proselytizing spills over into the political realm, with at times growing world-wide restrictions on religious freedom and the right to proselytize.

The stark repetition of the admonition to being of one mind in the first and last phrases is particularly arresting, and particularly challenging for us today. After all, for contemporary liberalism, being of one mind is no virtue, and the same could be said for most contemporary Christians. We no longer think of pluralism as simply a pragmatic political strategy for negotiating irresolvable difference, but as a good in itself. It is difference, we say, that makes us strong, tolerance and indeed embrace of otherness.

. . . As you can tell from the course description, I even started the course by asking, in effect, “Why are people using this term?” I’m still not sure that I know the answer to that question almost five years later. In teaching the course, the question of the academic worth of the material was at the forefront of discussions during the entire semester. “What was wrong with liberalism again?” was a question that, sometime around week six, took on full zombie status: it would just not die.

. . . Often much more important than what people argue is how people argue. . . . Many whom we may have hastily taken as kindred spirits, because they happen to have reached some conclusion we moderns take for granted, turn out on closer inspection to have been motivated by wholly different concerns, so that the convergence is largely illusory. Others, however, whom we might be apt to dismiss as barbaric for their unenlightened ideas, turn out to have been strikingly liberal-minded.

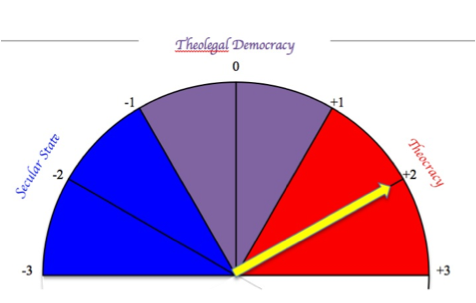

The United States is comprised of a religiously diverse citizenry, which leaves officials to balance the tension upheld by a constitution that simultaneously prevents the establishment of a national creed and yet preserves one’s right to freedom of religion. In practice, officials in the United States cannot legislate theology, but they can, and do, use theology to legislate.

As a result, the United States is not a secular democracy where laws guarantee freedom from religion and dismiss theological rhetoric in the political process; neither is it a theocracy, where a single religion prescribes all laws. Whether we like it or not the United States is a theolegal democracy.