Alastair Roberts

Essays

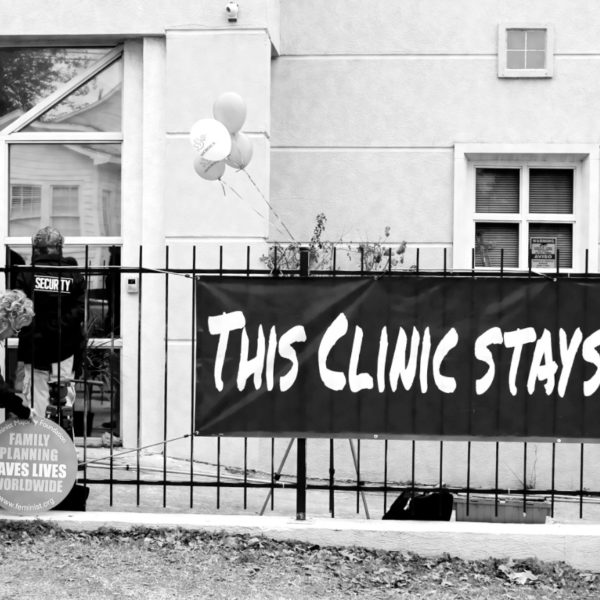

True ritual is a searching indictment of all injustice, a corrective for it, and a model for righteous behavior. Presenting ourselves before God in our ceremonies, we invite his inspection of the entirety of our lives; recognizing this fact, we must comport ourselves accordingly in all that we do. Civil religion and cultural religiosity will betray all those who put their hope in them.

The familiarity of the 23rd Psalm can blind us to the striking political dimensions of its message: YHWH is the shepherd of the king, protecting him from enemies and granting his kingdom prosperity. Close reflection upon this psalm may also suggest some significant applications within the contemporary world.

The story of the sign given to the shepherds—the Child wrapped in swaddling clothes, laid in a manger—both recalls and anticipates other scriptural events in significant yet surprising ways. It also reminds us of our vocation, as those who must declare the good news of the sign of Christ to the shepherds of our age.

Psalm 8’s presentation of human dominion and politics as a creation of God has significant ramifications for our posture towards the various forms of human rule and authority. The juxtaposition of divinely appointed power and human weakness humbles arrogant ambition, encouraging a spirit of meekness and modest service in our politics.

Christian political witness must be built around and declare Christ as the great eschatological stone laid by God. He must either be approached as the stubborn obstacle, arresting the development of all idolatrous political visions, or as the chief cornerstone, the sure and solid basis from all else can take its bearings.

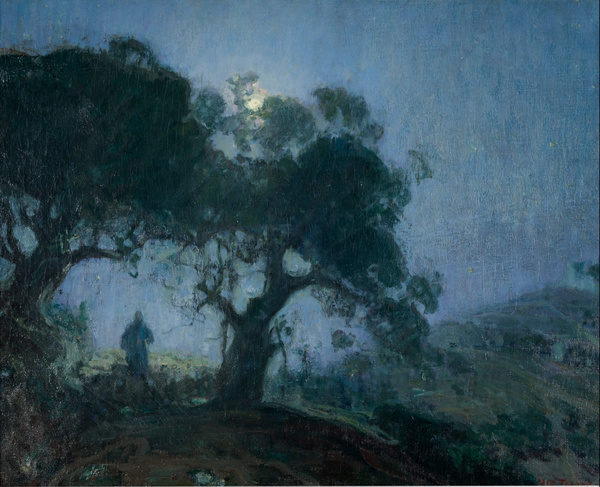

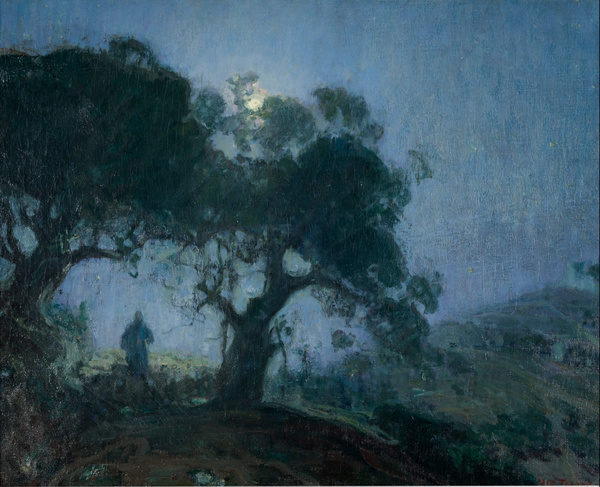

A competent sentinel must be vigilant, alert to and able to read the faintest signs upon a distant horizon, perceiving the most miniscule of details and discerning their greater import when they finally appear. In the opening chapters of both Matthew and Luke, we encounter a series of watchers and signs, presented in part as examples to the readers of the gospels in their own watching.

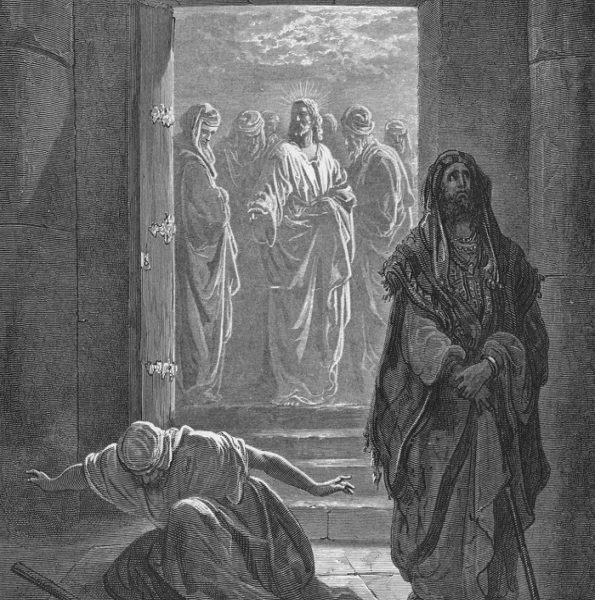

The Parable of the Pharisee and the tax collector is situated against the backdrop of the promise of the coming kingdom and the vindication of the righteous that will come with it. We too can look for future vindication and Jesus’ parable may speak to our own convictions about being on the ‘right side of history’.

As in the case of the unjust steward in Luke 16, a radical change in our handling of money is required, if we are to survive the great day of accounting that is to come. We must use the limited time and opportunity remaining to us to escape the clutches of our greed and expend our dirty money to pursue true and incorruptible riches.

In the narrative of Abraham’s conversation with God concerning the destruction of Sodom we find an example of the faithful fulfilment of the calling of the people of God. We are to be those who seek to preserve the world from condemnation by our righteous and life-giving presence within it, tenaciously refusing to abandon it to its destruction.

Proverbs presents a vision of political wisdom that calls for deep moral integrity of political actors, both in their most public and in their most private behavior. It offers an alternative to the cynical demoralization of contemporary entertainment-driven politics, with its celebration of permission and transgression.

In maintaining a faithful Christian presence in the political realities of this age, few things are more important than living and acting in God’s good time, being people who find their life in the living memory of a sustaining past, who patiently wait in hope for a promised future, and who are kept in the present through faith in the daily mercies of One who is the same yesterday, today, and forever. Christ’s institution of a memorial helps us to do just this.

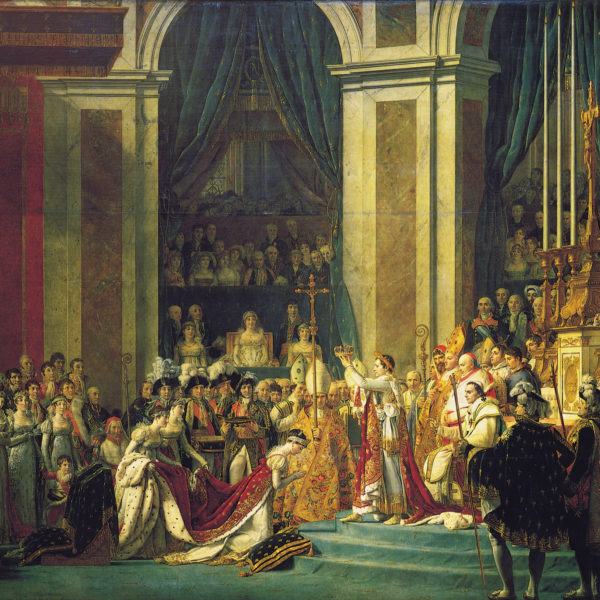

Spectacle has always played an important role in establishing power, authority, and sovereignty. In the unity of the dazzling body of the Transfiguration and the brutalized body of the crucifixion, the integrity of the spectacle and that which lies beneath is made known and our own polities’ lack of such integrity is challenged.

Paul’s argument that spiritual gifts are the manifestation of the one Gift of the Spirit, given for the service of the common good, provides a useful starting point for reflection upon the meaning of representation in society more generally. The ecclesiological vision of 1 Corinthians 12 resonates in challenging ways in our polarized political cultures, summoning us to new modes of engagement.

The political significance of Paul’s charge to the Colossians to give thanks to the Father in all things that they say and do is surprising in its far-reaching implications. The proper direction of our gratitude to God, the giver of all good gifts, limits the power of those who would dominate by indebting others, encourages us to release others from their debts to us, and frees us to give to those who cannot repay: it is one of the most radical political actions the Church engages in.

As political theologians we may be peculiarly vulnerable to the error of neglecting—or even denying—the significance of the obscure and personal struggles and victories of the faithful that do not assert themselves onto the grand public stage of society. We have much to learn from Hannah’s recognition that, in God’s answer to her prayer for a son, the seeds of a dramatic social and political upheaval had been sown.

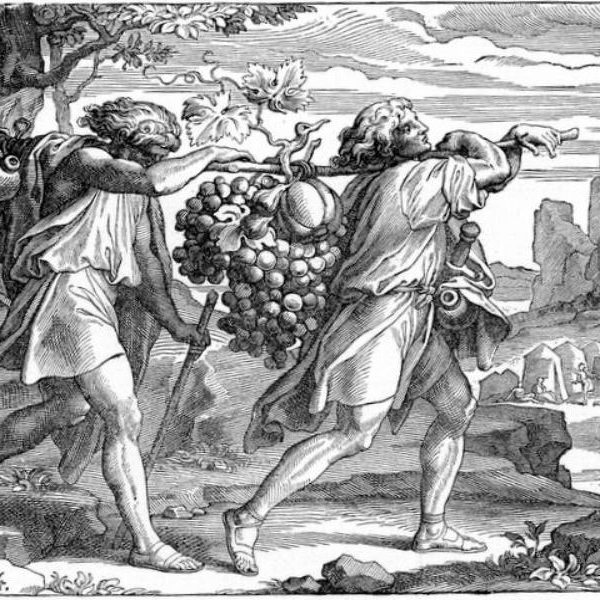

Moses taught Israel that its primary calling as a people before the nations was not conflict but witness through its showcasing of the goodness, wisdom, and righteousness of the divinely given law. Likewise, the chief political task of Christians is found in the cultivation of a quiet extraordinariness in the most ordinary affairs of life.

The familiarity of the 23rd Psalm can blind us to the striking political dimensions of its message: YHWH is the shepherd of the king, protecting him from enemies and granting his kingdom prosperity. Close reflection upon this psalm may also suggest some significant applications within the contemporary world.

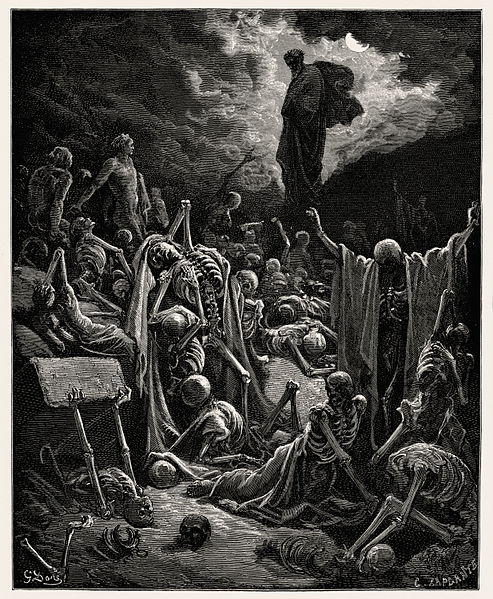

The promise of the new covenant in Jeremiah 31:31-34 contains political dimensions that typically pass unrecognized, but which provide a rich description of an ideal polity. This prophetic vision can serve as a powerful counterpart and companion to more conventional political utopias and idealized societies.

At moments of crisis, it can be the responsibility of committed individuals to secure and represent the self-understanding of the community or nation to which they belong, to provide the seed from which the entire social body can be renewed. Within easily neglected political dimensions of the baptism of John we may be recalled to our potential and vocation as political individuals in this regard.

Privilege is a ubiquitous reality in our world, though one to which we are often oblivious as privileged persons. In Paul’s description of his posture towards his privilege he gives us a worked example of what conformity to Christ can look like and poses the challenge to us to follow the same path in our own situations.

In the Passover we find a myth of the foundation of a nation that differs markedly from the contractarian myths of the Western liberal tradition. It disclosure of the sacrificial basis of the political order offers us a hermeneutical key for understanding the roots of our own nations and helps us to understand how we might be established as communities of faithful witness to them.

Isaiah offers us a startling vision of a society beyond scarcity and gross inequalities of wealth, leading to a subversion of all our economic logic. If we are prepared to re-conceive our world as a divine gift to all, we will be prepared to work towards a day when no one is excluded from God’s bounty.

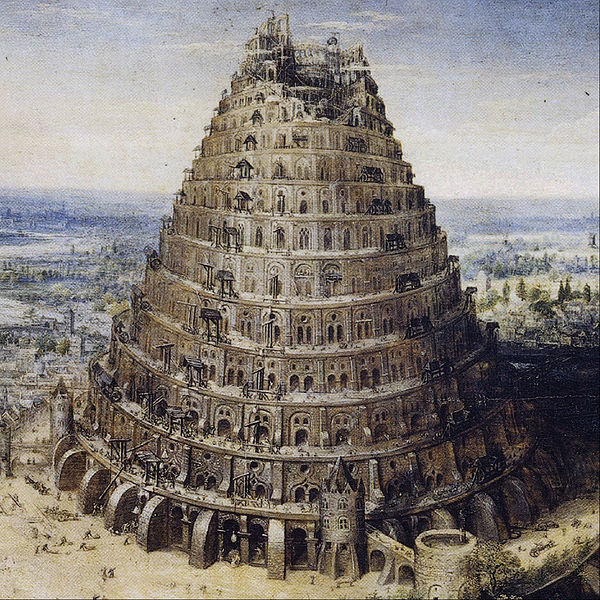

As the people of Pentecost, our political vocation is to manifest the reality of God’s worldwide kingdom, to be a place where the enmity between peoples is overcome and the many tongues of humanity freely unite in the worship of their Creator. Amidst the Babelic projects of the ages, the Church proclaims by its existence that the kingdom belongs to God, that there is no other true ruler over all the nations.

In the face of the thoroughly known god who sponsors our political ideologies and patriotic projects, we must join with the Apostle Paul in proclaiming the unknown God. Cutting across our speculation, superstition, and listless curiosity in the revelation of Jesus Christ, this God punctures our comfortable idolatries and calls us all to give account.

The encounter of Mary Magdalene with the risen Christ provides us with a model for understanding political theology. The elusive presence of the resurrected one and the emptiness of his tomb forbid all our attempts to secure his presence in our praxis and open up new ways of perceiving our social task.

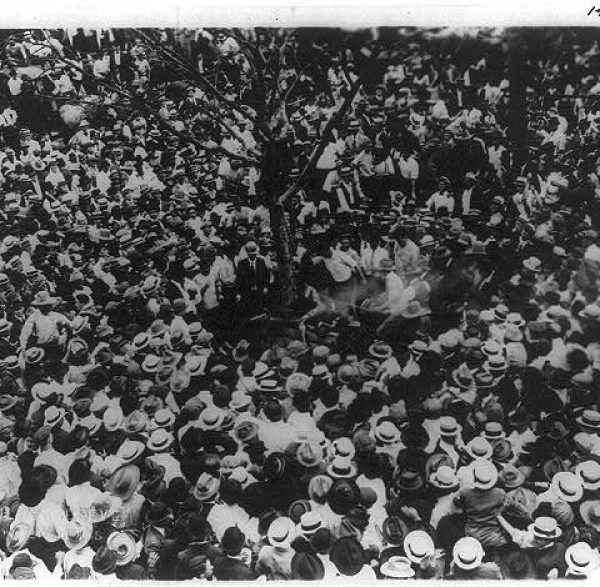

The contagious violence of a frenzied mob brings about the sentencing of Jesus to crucifixion by Pilate. The operations of the scapegoat mechanism are revealed in the record of these events and, as we reflect upon them, we will learn to identify its operations within our political life. In Christ we find an alternative model for desire, which can enable us to resist the seduction of unity through violence.

The growing power of government to trace everything that we do and to reveal our most compromising secrets has been an increasing source of public concern over the last year or so. In Jesus’ encounter with the Samaritan woman at the well we see an example of such omniscience employed to liberate, rather than to enslave. While such godlike power in the hands of our governments is a scary prospect, in God’s hands it need not be a cause of fear.

The contemporary exploitation of word of mouth in political and advertising campaigns on social media can encourage a degree of cynicism. At the outset of Jesus’ ministry in John 1:35-51 we see an account of the use of word of mouth that overcomes scepticism and rewards trust. This can provide us with a standard and ideal for our own involvement in political campaigning.

In Isaiah’s prophecy a young child serves as a sign puncturing the gloom of a dark political situation. The use of infants and young children to draw attention to God’s future within the book of Isaiah has significance for our own political visions. In regarding the sign of our children we can accomplish an existential turn from a politics driven by the selfish interests of our own generation to one of responsibility and hope for the well-being of those to come.