It is impossible for me to watch the footage of the children killed by chemical weapons in Syria without feeling a lack of coherence with the world. We were not meant for this. They … they were not meant for this. Their parents were not meant for this. The world was not meant for this. Breath, the source of life, was turned against these children. Their lungs were filled with death.

In his When War Is Unjust: Being Honest in Just-War Thinking, theologian John Howard Yoder asks, “Can the criteria function in such a way that in a particular case a specified cause, or a specified means, or a specified strategy or tactical move could be excluded? Can the response ever be ‘no’?” (Orbis 1996, p. 3) In my judgment, the present crisis in Syria is indeed a particular case where a just war response is “no.”

I don’t know precisely when I first met Jean Elshtain. I think it was in the summer of 1995, in Swift Hall, home of the University of Chicago Divinity School. I must have been told of her arrival by one of the faculty. I know I talked to her in the corridor, that most important of places to ambush your teachers, and decided after that chat, that I would sit in on her class that Fall term—entitled, as I remember it, “Beginnings.”

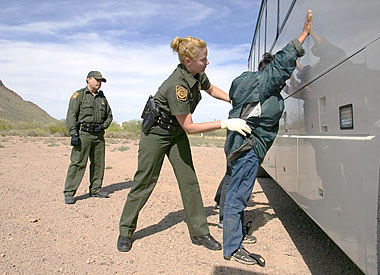

In the public debate surrounding the U.S. Senate’s bill proposing the reform of the immigration system, and now the House of Representatives’ efforts to craft its own bill, one is bound to encounter the argument that falls under the label of “enforcement first.” The argument goes that before the illegal immigrants who are already present in the U.S. gain any sort of legal status, we must first put in place measures that will ensure that in the future, further illegal immigrants do not enter the country in the hopes of an inevitable legalization process at some point in the future. This argument is flawed, and if it were put into practice would prove costly and harmful to immigrants without solving the illegal immigration problem.