The prophet Isaiah was a city dweller, but his mind was on the countryside. Trees, vineyards, and fields populate his thinking and that of his successors in this long book, where vegetation serves both as metaphor (as in Isaiah 5:1-7), and as the life-sustaining growth on which humans literally depend (as in vv. 8-10). Agricultural imagery appears from one end of the book to the other (1:8; 66:17), spelling out both judgment and hope.

Can a people, after having duly consented to the formation of its government, remove that government using procedures not authorized by law? To put the question differently: can the formal legitimacy that a people provides a government preclude that people from exercising its sovereign power to strip those holding formal legitimacy of power, even though those in power have not violated the express terms of their compact with the people? These are the paradoxical questions that are at the heart of the political crisis in Egypt where duly elected president, exercising powers pursuant to a duly enacted constitution, was overthrown by the “people” who acted outside the formal rules “the people” had enacted for removing or otherwise disciplining its president.

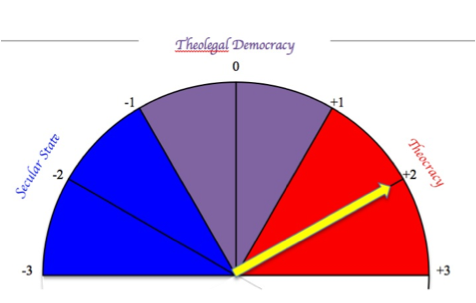

The United States is comprised of a religiously diverse citizenry, which leaves officials to balance the tension upheld by a constitution that simultaneously prevents the establishment of a national creed and yet preserves one’s right to freedom of religion. In practice, officials in the United States cannot legislate theology, but they can, and do, use theology to legislate.

As a result, the United States is not a secular democracy where laws guarantee freedom from religion and dismiss theological rhetoric in the political process; neither is it a theocracy, where a single religion prescribes all laws. Whether we like it or not the United States is a theolegal democracy.

I join this conversation as a student of comparative politics, writing a project that explores how islamiyun, often dubbed Islamists, imagine and enact democracy. Specifically, I use insights derived from ordinary language philosophy to apprehend insights from interviews and focus groups with over 100 interlocutors, gleaned in nearly two years of fieldwork in Morocco (2009-2011), to understand what democracy means to Moroccan islamiyun. I find that there are two broad usages of dimuqratiyyah [democracy] in the language and practices of Moroccan islamiyun.

I want to argue here that the term “political Islam” is in many ways a misnomer, because the Islamism that is meant to instantiate it has been unable to appropriate politics as a way of dealing with antagonism either institutionally or even in the realm of thought. Looking in particular at the form Islamism took with one of its founding figures, the twentieth century writer, and founder of the Jamaat-e Islami in both India and Pakistan, Sayyid Abul a’la Maududi.

I join this conversation as a political theorist having just published a book, Beyond Church and State: Democracy, Secularism, and Conversion (Cambridge 2013), in which I argue that the modern secular imaginary is premised upon an insufficient image of secularism as the separation of church and state, and that secularism should instead be understood as a process of conversion that reshapes key dimensions of both religious and political life

Although Meghan Clark and Joseph Tetlow, S.J. have raised some important criticisms of Stacie Beck’s contention that the “social justice agenda” of many Catholics ignores certain basic truths of capitalist economics, they downplay the extent to which the provision of certain basic human rights is dependent on the creation of wealth. The Catholic philosopher Jacques Maritain provides guidance on how to maintain both the grounding of human rights in universal human dignity and the contingency of concrete rights, a balance necessary in the current age of austerity.