Two questions stand out: Why was Michael Brown killed and why are police units increasingly militarized so that they resemble soldiers in a war zone more than cops on a beat? The answers to these questions do indeed lead back to government–not simply to “big government,” but to a bureaucracy directed to wage war on a class of its citizens, driven by a political culture that ironically champions law and order.

…Stalin is unique among world communist leaders in at least one respect: he studied theology for five years at the Tiflis Spiritual Seminary, the training college for priests in the Russian Orthodox Church. He did so during a deeply formative time of his life, from the age of 15 to the verge of his 20th birthday (1894-1899). One of the best students, he was known for his intellect and phenomenal memory.

Perhaps part of the reason why disparities in food distribution continue to exist is that, when those of us who have food enough on our tables try to respond to disasters such as famine, without connection with the people who suffer them, both they and us are likely to come away empty. The ironic use of famine in Naomi’s story is able to suggest to us another way, an approach to famine that sees first the emptiness in relationships when kin from the ‘developing’ and ‘developed’ worlds find ourselves absent from one another.

When Israel launched Operation Protective Edge in response to cross-border terrorist rocket-fire, European (see here and here) and US leaders endorsed their claim to have just cause. But were they right to do so? Do the on-going attacks conform to just war criteria? These are separate questions; both are important. We seek to address these issues from the perspectives of international law and Catholic theological ethics.

In the sphere of political decision-making, ‘the grace of doing nothing’ is usually a losing proposition. However, the parable of the wheat and the weeds invites even the angriest reactionary to consider the complexity of wheat and weeds, good and bad, us and them, and the dangers involved in precipitous action.

. . . The underlying structural crisis does not seem to have gone away. Indeed, in the last year and, more perspicuously in the past two weeks, it has found a more demanding as well as disquieting focus — student debt as well as the economic albatross of the maturing millennial generation itself. . . . The real scandal is the monstrous moral hazard that the student loan lending system has spawned. It amounts, according to Taibbi, “a shameful and oppressive outrage that for years now has been systematically perpetrated against a generation of young adults.”

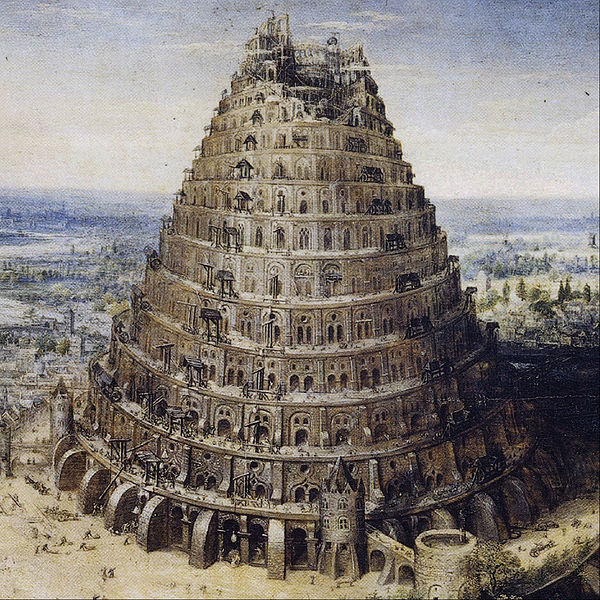

As the people of Pentecost, our political vocation is to manifest the reality of God’s worldwide kingdom, to be a place where the enmity between peoples is overcome and the many tongues of humanity freely unite in the worship of their Creator. Amidst the Babelic projects of the ages, the Church proclaims by its existence that the kingdom belongs to God, that there is no other true ruler over all the nations.

Within many criminal justice systems, deterrence is a significant element of the rationale of imprisonment. However, Paul’s letter to the Philippians reveals the emboldening power of imprisonment for faithful witness. The example set by courageous leaders who will risk imprisonment for the sake of truth and justice continues to have great power, even within our contemporary situation.