The editors of Political Theology are pleased to announce that Vincent Lloyd of Syracuse University is the newest member of the journal’s editorial team. Lloyd agreed to join the team as one of the editors beginning November 1. He had been a frequent contributor to both the journal and a contributing editor to this blog. Below is a short bio as well as links to more about Lloyd’s research and his book, The Problem with Grace…

Marriage equality is a hot topic in Christian communities. Recently, Gene Robinson, the first openly gay bishop, came to Fuller to talk about the freedom to love. As a result, many students at Fuller are beginning to rethink their heteronormative understandings of marriage. While I am all for LGBTQ equality in all arenas (anything else is shenanigans), the resurgence about the right to marry and marriage as an existentially important institution worries me […]

Presidential candidates Barack Obama and Mitt Romney have both focused on the middle class, but Christianity demands a preferential option for the poor. Christians of the Left and the Right should be able to find common ground on policies to help the poor. Here are five policies that could serve as the basis for such a common ground.

Understanding the relationship between morality and religion has preoccupied humanity’s best and brightest for millennia (think Plato, Aquinas, Kant, Nietzsche). Today, fascination with questions of morality and religiosity is no longer confined to philosophers, theologians and religion scholars. Research into the various ways that religion might influence moral identity is underway across a variety of subject disciplines in the human, natural and social sciences, capturing the interest of biologists, geneticists, neuroscientists, psychologists, anthropologists, and sociologists. Such research is highly necessary. The vast majority of the seven billion people on the planet identifies as religious. Most adopt at least some social and cultural norms and practices that reflect their religious identities. Across the globe, countless moral choices, great and small, are made on the basis of religious faith….

The number of people in the U.S. living below the poverty line in 2011 was 46.2 million, the highest in the more than 50 years that records have been kept.[i] (1961 is a few years before Lyndon Johnson’s “War on Poverty,” and about seven years before the Southern Christian Leadership Conference organized the “Poor People’s Campaign” that would take Martin Luther King, Jr. to Memphis.) Why then is so little attention being paid to poverty and poverty-related issues in the current presidential campaign?…

The ongoing riots and demonstrations throughout the Muslim world to protest a onetime obscure and amateurish movie made in Los Angeles have impressed on the Western secular mind that religious fervor, even if its expressions are frightening, is a growing planetary force to be reckoned with. What Derrida in 1993, miming Freud approximately two decades ago during the run-up to 9/11, dubbed “the return of religion” is a reality with which secular liberalism has had a hard time reckoning….

There is no shortage of elements in Romney’s statements to investigate. In particular, his ridiculously inaccurate statements about taxes are being addressed by journalists and analysts like Ezra Klein in today’s Washington Post. But behind his statement about victimhood and the dismissal of almost half the country as dependent upon the government without any contribution to civil society is a revealing ideology of the public order that I find most disturbing.

There is a sense when one steps into the produce section at the Whole Foods that one has entered a sacred space. The delicate ambiance created by the well-tuned lights and the gentle purr of background music cloaks the organic kale in an almost mystical aurora. Like a church service, Whole Food’s shoppers dress for the experience, donning bright shades of Yoga pants, organic slippers made with bamboo reeds, or any locally-made organic cotton tee—in a concerted effort to show the completeness of their healthy and ecologically-sensitive lifestyle. Moreover, when they reach the checkout line and fork over what for many normal folks amounts to a whole paycheck, the acolytes gently absorb this small sacrifice as doing their part for the environment and their bodies….

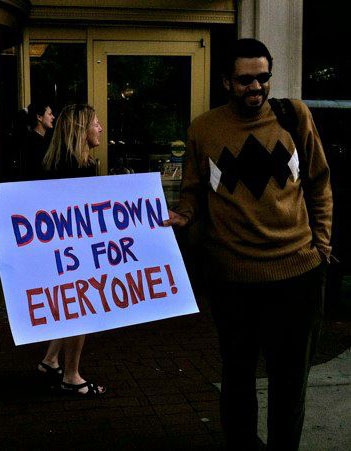

With this sort of starting point, we take an altogether different approach: our task, short of the full in-breaking of the Kingdom of God, can never be any partisan agenda. This is because anything short of the full consummation of the Kingdom of God will necessarily still be tainted, or worse, corrupted, by sin. All political activism then—in the sense of being active in talking to the contemporary powers-that-be in western culture—is always and necessarily ad hoc, never utopian, and never idealistic. We deal with each concrete question and issue as it arises, and seek to bear faithful witness as best we are able.

Inter-religious understanding and debate, once neglected within the academic study of theology and religion, has acquired a political significance that is unlikely to diminish in the foreseeable future, with the result that it will require substantial and sustained scholarly engagement and investment for the long-term.

The focus of the current issue of Political Theology (13.4) is religious pluralism, and inter-religious dialogue and cooperation. Overlooked and marginalised for too long in the academic study of theology and religion – where the ‘big beasts’ of the discourse have tended to be scholars pre-occupied with intra-religious concerns, and where expertise in religions in the plural has been frequently regarded as stretching yourself too thinly – such studies are slowly assuming an academic importance commensurate with the geopolitical significance of religion…..

We face a seductive fantasy of independence from a wider, dynamic order of things, with the result that our response to challenges in international relations or ecological crisis have been rather consistently out of touch. But of course this is far from simply an American problem. I suggest that it stems from a disease of the modern subject, a way of looking at the world that treats “its” objects as inert and easily manipulated. In other words, this is a deeply-rooted metaphysical problem, a constitutional failure to account for the capacity of objects in the world to push back…..