For me, “political theology” thus names the study of the ways that imagination is embedded in sentient, desiring bodies, instantiated in vernacular forms of life and ordinary (ritualized) practices, and conjured in mytho-poetic metaphors, images or representations that are formalized by literary genres and assembled into scriptures.

Even the highly professionalized logos of scholarly discourse does not just suffer from logoclastic dynamics but is positively animated by them.

Situated on this eschatological middle ground, political theology must reckon with how we live in a time when the kingdom of God is present, creating moments of transformation and rupture…To speak truthfully, political theology must also speak to the quotidian joys and everyday struggles that make up the ordinary time of our lives.

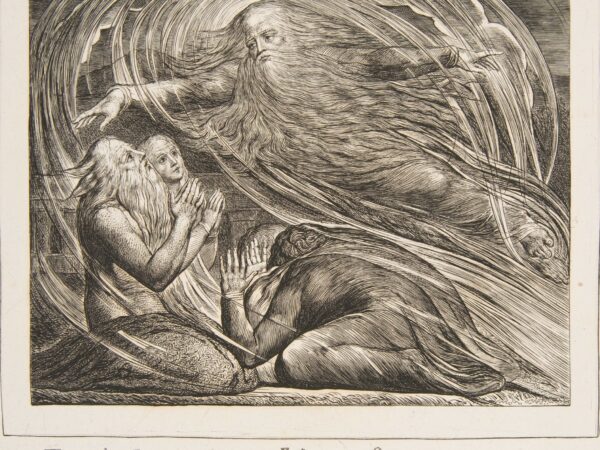

A competent sentinel must be vigilant, alert to and able to read the faintest signs upon a distant horizon, perceiving the most miniscule of details and discerning their greater import when they finally appear. In the opening chapters of both Matthew and Luke, we encounter a series of watchers and signs, presented in part as examples to the readers of the gospels in their own watching.

Political Theology and the lectionary for Sunday, November 20, 2011.

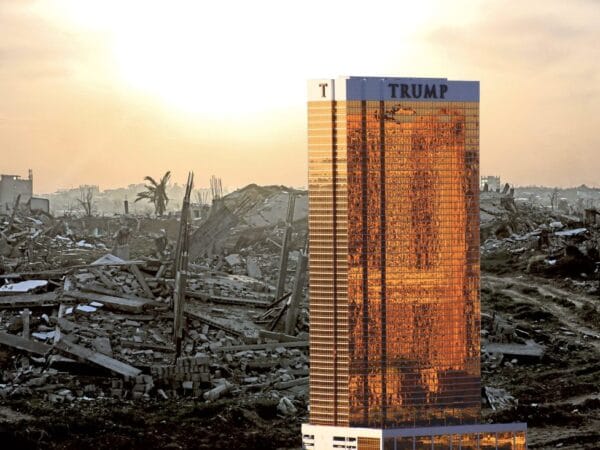

To be sure, some smart evangelicals like Chuck Colson have abjured Rand in toto for her atheism, but her basic premise that government is the root of all evil and that unfettered capitalism is the answer for everything is as true as Trinitarianism in most evangelical’s minds and hearts, a position all but unheard of in Christianity prior to the 20th century.

To think this way as a Christian, one has to do strange things with the Scripture, such as with this week’s lectionary gospel passage for Christ the King from Matthew 25:31-46. The obfuscation of what’s going on in the text is accomplished by diminishing one aspect of the text, while overemphasizing another.

This text is one of the most fruitful lessons for thinking about the political theology of scripture in the whole three-year cycle. It is also one of the most humorous texts in scripture, as the powerless subvert the powerful.

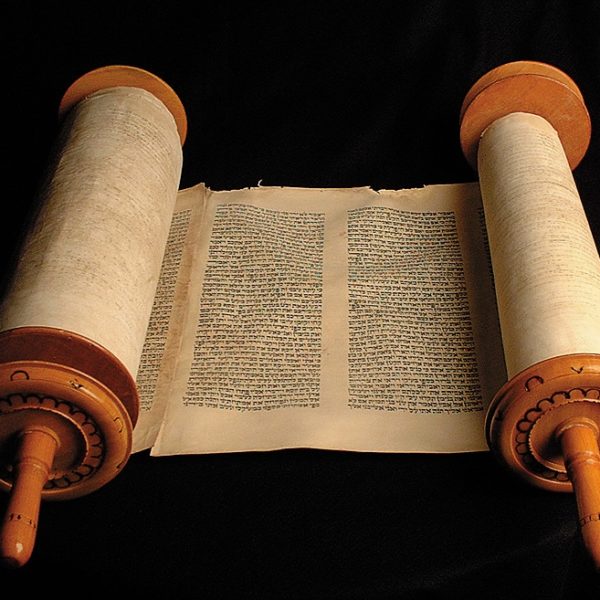

[The the second of three posts this week on Michael Walzer’s In God’s Shadow: Politics in the Hebrew Bible.] It is deeply satisfying to read a new book by Michael Walzer on the Hebrew bible. Certainly this is not Walzer’s first book on the Hebrew bible: Walzer’s earlier Exodus and Revolution already gives us a unique way to reimagine the revolutionary implications of the biblical text. With this new volume, Walzer’s writings on the bible continue to invigorate the way we can read this most ancient of texts. Michael Walzer’s In God’s Shadow sets a difficult task for itself. It reads the wide-ranging Hebrew bible to get a sense of how political institutions actually functioned in biblical times. This enterprise is more difficult than it sounds. Mining a work that consciously centers on historical and legalistic narrative for structural and procedural understandings about how political life actually works can be a counterintuitive project. It is a tribute to Walzer’s masterly sense of his craft and his nuanced readings of the biblical texts that he succeeds so well at his self-appointed task. Deliberately eschewing a philosophical or reductive (morally or otherwise) reading of the Hebrew bible, Walzer approaches these much-commented texts with another set of questions in mind: what role is left for politics in a world that, according to the bible at least, is governed by God?

Samuel speaks of God as working in and through the events to deliver “ruin on Absalom.” This is not simply God with us. It is God against us–whenever we treat our “kingdom” as if it was ours and ours alone. Both David and Absalom acted as if their people, the Kingdom of Israel, were their own plaything.