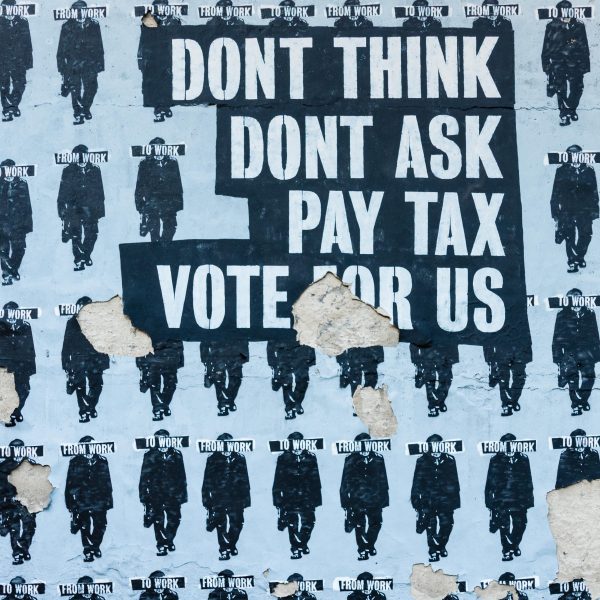

Jesus’ teaching regarding taxation and our allegiance to human governments challenges Christians who find themselves subject to contemporary governments to think about how we relate to their inevitable exploitation.

Efforts to leverage “God” are often attuned to the dynamics of the symbol yet remain largely untroubled by the gaps such acts generate.

In the wake of an atrocity such as the San Bernardino shooting or the attacks in Paris, the choice between the politics of righteousness and the politics of fear will press upon us with a renewed urgency. However, it is righteousness—justice and ethical probity—that is the only genuine answer at such a time.

Wisdom’s publicly raised voice challenges the simple ones, who love being simple; the scoffers, who delight in their scoffing; and the fools, who hate knowledge. The reproof of Wisdom is especially relevant in the contemporary political world, where so many of our leaders and politicians thrive upon such popular attitudes.