What happens when kings and rulers are confronted by a child whose very presence boldly proclaims that God is with us? Sometimes children have an astounding ability to disrupt the status quo. They resist passivity and compliance, they dream boldly and they demand justice. Who are our Immanuels today? And what do we do when we encounter them?

How do we then understand a biblical vision of peace relevant for our contexts today? Peace, from a decolonial theological perspective, is not a mere act of non-violence, nor is it about drawing peace plans from the perspective of the powerful global powers; rather, it is about the holistic well-being of the whole creation, coupled with justice, where life matters.

What if Zephaniah’s addressees had a right to mourn, lament, and rage against the wrath of Yhwh? Afterall, Yhwh’s favor is fickle in Zephaniah, entirely contingent on a particular obedience and only coming after the divine wrath is spent.

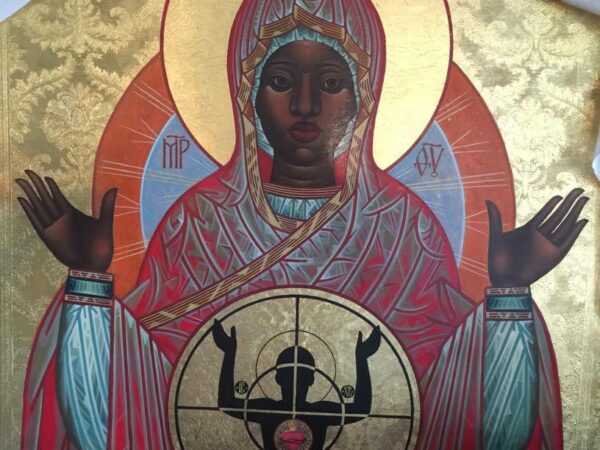

The Magnificat is a song that disrupts both gender and hierarchical spaces. It is a song of anticipation and a song of realization. And as we meditate on this song during advent, we meditate on the nature of advent that is both a time of anticipation and realization. Advent is an ambiguous space that invites us to anticipate and realize the erasure of differences here and now.

The Gospel of Mark’s beguiling beginning bids us to consider the dangers of beginnings. John the Baptist’s heralding of Jesus’s coming was not the finality of salvation, but merely a herald to its coming. In this light should we consider our works of bringing God’s salvation and liberation to the world. The work of justice and liberation is long and hard, and many of us will be called to herald it, to lay the groundwork for its eventual manifestation.

In the midst of a pandemic, can these Advent texts speak to our grief, both collective and personal, in political ways? These scriptures reveal that to grieve is to bear witness to our tears through righteous anger. They interrogate how our lives are structured along inequitable lines in this present moment and counter a simple return to how things were.