In a time of intense economic anxiety, both individuals and communities need to reflect on the call in John 12 to claim their responsibility to shun greed, resisting it with a seemingly foolish kind of generosity that parallels Jesus’s becoming poor for the sake of others.

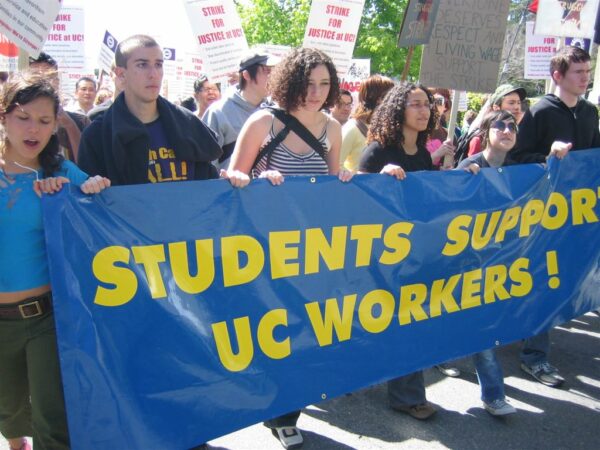

A Pentecostal revival of justice would bear all of the hallmarks of Luke’s story. In quick order the Spirit-driven church of Acts established a community where nobody was lacking. A revival today could bring that same ecstatic joy and establish a community oriented toward justice.

I have been interviewing thirty persons, mostly forcibly-terminated professors from Protestant and Catholic institutions, and several professionals who work with them. Their stories demonstrate a stunning depth of disillusionment. The majority of these often-ordained religionists feel so betrayed by the church that they – and often their families – refuse to be part of it anymore.

This Christmas season, what might it mean to live into the promise of hope fulfilled, when our pandemic experience means that hope strains against lost lives and lost livelihoods? Perhaps it involves visioning a redemption—one built on the social and economic implications of Jeremiah’s vision of those redeemed.

A second expression of relationality is covenant. It is a bond between distinct parties where each gives for the flourishing of the other. Unlike contract, which protects interests, covenant protects relationship.

Rendering to God what was God’s meant offering our lives as living sacrifices of worship to God, as one would offer coins as tax and tribute to one’s sovereign. The human was theologically monetized—or coined—in the name of dedication to God.