The Spirit is the decisive factor in any ethical and political existence that would strive for truth, for justice, and for a mode of persuasion that can challenge the world’s assumptions of what is possible without rhetorically pulverizing those who do not yet agree or pretending that we are better or wiser than we really are.

“I was only imagining it. Being freed.”

In this hymnic account of Jesus’ person and mission, his preference for and service to others becomes a paradigm for faithful human existence. God’s solidarity with the human race discloses the truth of both power and freedom.

Luke’s wordplay allows us to see this story as something larger than a particular Jesus event with a particular woman in a particular synagogue on a particular Sabbath. A one-off, straightforward healing event can be described without such wordplay. Through the creativity of his storytelling, Luke makes this moment a signal event, about a Daughter of Abraham and the work of the Christ.

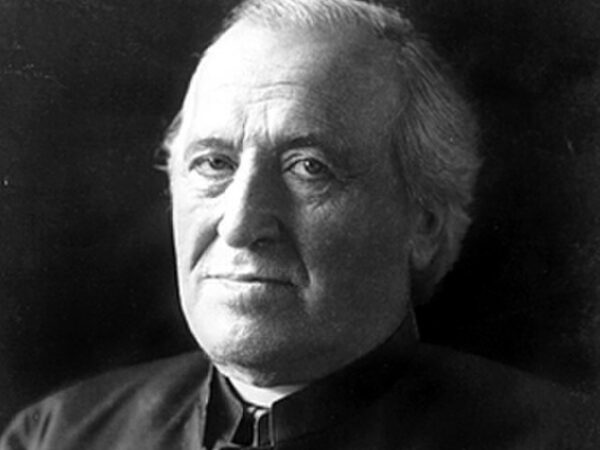

Using the example of nineteenth-century “Americanist” archbishop John Ireland, and his boarding school initiatives in Minnesota, this essay demonstrates how the US Catholic Church came to behave as an American institution by seeking common ground with liberal ideals of freedom, while simultaneously embracing state policing and punishment against populations marginalized from the body politic.

The primacy of the inner type of freedom can produce a withdrawal from the world or an attitude of passivity towards its frustrating circumstances, particularly when the believer searches for real freedom exclusively inside the self irrespective of the conditions that exist in the broader socio-political environment.

“Seek ye first the political kingdom of God and all these things shall be given unto you.”