The grass seemed greener in Orthodoxy, I’ve realized, because my yearning for authenticity and escape reflected a structural lack embedded in late capitalist dystopia… Today, it seems to me more honest to learn to live with this lack, than to imagine that any faith, flag or folkway can fully fill it.

Whether through suits before the International Court of Justice, pro bono suits in American courts, appeals to the United Nations, or student-led civil disobedience movements on campuses all over the democratic world, Palestinians and their supporters are attempting to cause a miraculous rupture in the realm of positive law, not to further the arbitrary ends of power, but to further the just and lawful ends of Palestinian freedom.

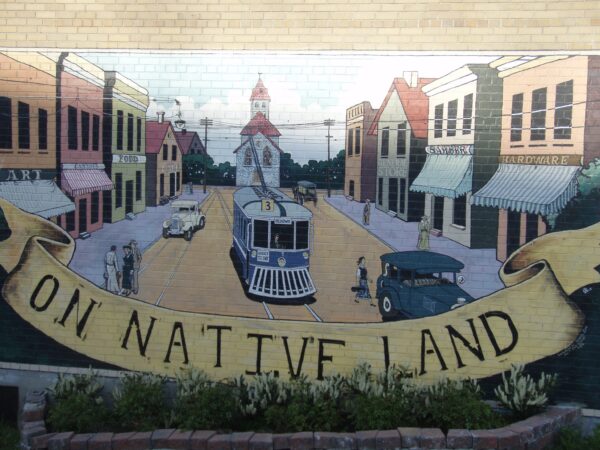

From the perspective of political theology, the presence of Indigenous peoples and settlers shaped by historical and ongoing settler colonial relations raises important political and religious questions about the possibilities and conditions of sovereign Indigenous existence and the (im)possibities and conditions of restorative or reconciled settler futures.

Whatever our exegesis of scripture and tradition may suggest, it is imperative that we take into account the pain and damage our religious piety causes to others. Is our perception of divine instruction sufficient justification for actual injury (physical, psychological, and/or spiritual) to our neighbors?

Since World War II, the primary ambition of international humanitarian law — the law of armed conflict — has been to insulate military violence from the civilian population. Military forces are required to identify themselves as such, by wearing clearly marked uniforms, and to discriminate in their selection of targets: They cannot deliberately attack noncombatants or infrastructure that has no military use.

I wish to thank Dr. Bernstein for his thoughtful and irenic response to “Zionism Unsettled” (hereafter, ZU). . . . ZU is indeed a hard-hitting document. It says things many people would rather not have discussed and calls out both Jewish and Christian Zionists for their contribution to the misery and suffering of the Palestinian people. Such a resource, which could be utilized at the congregational level, was sorely needed. The Israeli occupation began in 1967, when I was four years old. I’m now a grandfather, and yet it still continues.