In this present age, we are beset by people, inside and outside of the church, who are on an anti-tax jihad.

By Matt Lacey

We are presented with the question: are we called to be Americans first, or Christians first? Are we called to claim our heritage as our coincidental place of birth, or our Christian heritage that transcends political and continental borders?

The image I have is of a balloon which now has too many people aboard and that, in order to stay airborne needs to throw some of its passengers overboard. I say this as what I believe is now happening is that too many people have been able to benefit from global capitalist growth over the last 20 years and that in a period of austerity and economic downturn access to the “goods” of global capitalism is going to be limited and rationed.

I have been only sporadically involved in politics throughout my ministry, generally considering political engagement by clergy to be a decidedly mixed bag. My high calling as a preacher didn’t seem to mesh well with the grubby compromise demanded by democratic politics.Then the church sent me to be bishop in Alabama.

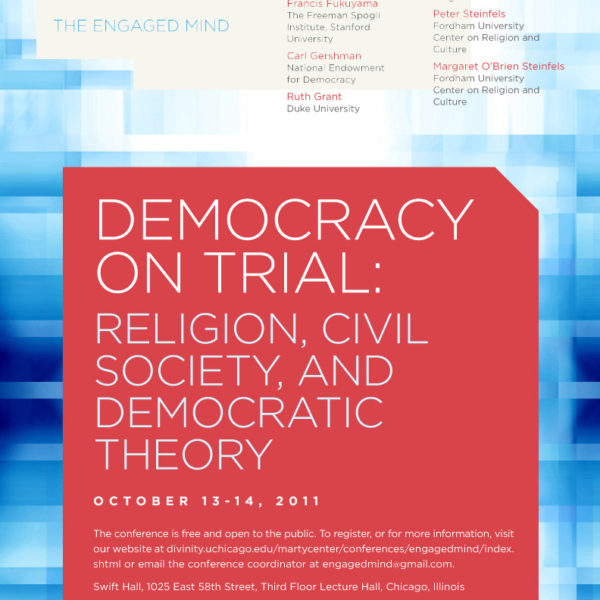

What is the state of our democracy? Is democracy good for the world? How does religion support or hinder democratic practice? Throughout her career, Jean Bethke Elshtain has challenged both liberal and conservative approaches to politics, emphasizing the crucial role that the mediating institutions of civil society play in a successful democracy. She has identified the forces that oppose democracy: identity politics, utopianism, and an elitism that denies ordinary people the prerogatives of citizenship. Yet she has consistently maintained a realism tinged with hope, pointing to Jane Addams as an exemplar of lived democratic practice.

The main problem is, we the people have given and continue to give it to them. Notice in the text that it is not Aaron who first announces that the calf is the god that delivered Israel from Egypt. It is the people themselves who identify this false connection, just as we ourselves are complicit in this perverse deification of injustice.

Locating a middle requires, first, the critique of ideology, which determines the options that appear before us. But the critique of ideology requires an attentiveness to tradition, and to social practices and norms. The “Continental” side talks a lot about ideology critique, but rarely does more than gesture towards those social realities.

In his final book, Why Niebuhr Now?, the late John Patrick Diggins exposes what he claims are false appropriations of Niebuhr and offers in their place Niebuhr’s critique of power. It is this insight, says Diggins, that is especially needed today. This is a significant argument, one worth discussing. And so we asked two scholars, Elliot Ratzman and Ron Stone, to help us launch the conversation.

Jesus says, “Have you never read in the scriptures: The stone that the builders rejected has become the cornerstone?” (20:42). Have you not heard that the poor own the kingdom of God? Do you not remember that the meek are blessed? Do you not remember that Christ is incarnate in the least of those among us? It is as hard for us to hear the cries of the poor today as it was for the Jesus’ fellow Jewish teachers and leaders to hear the voices of the tenants.

The Republic of Grace means to offer an extended account of why and how we, Christians and non-Christians alike, must learn to understand ourselves as continually, graciously, coming to be re-habituated, and recalibrated, into the grammar and language of love, even–and perhaps ultimately–in the public realm.