From Myanmar to Mariupol, from the streets of Memphis to the waves and winds of the Mediterranean Sea: resistance to violence takes many forms. So does political protest against precarity. At which point does the unavoidable vulnerability of the living condition come to expression as political agency? Can such precarious politics constitute or configure an alternative community?

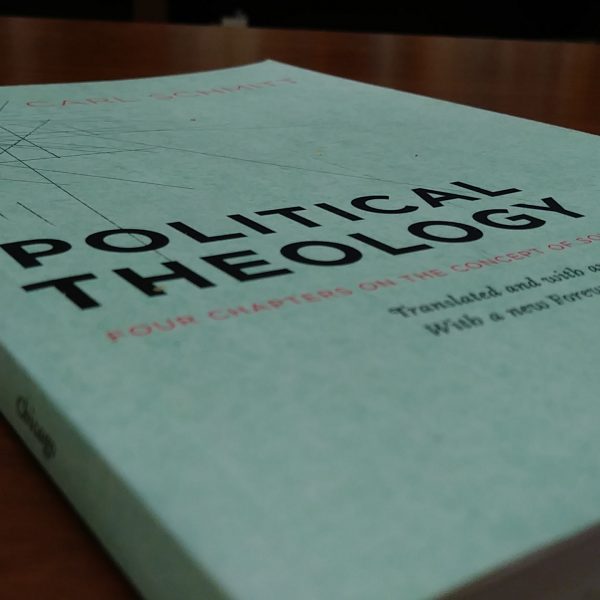

In the end, we think that this collaboration of journals has produced an interdisciplinary exchange that deepens and complicates categories of race, equality, citizenship, and belonging that are salient in different ways to the fields of Law and Religion and Political Theology.

Discourses around Muslims and Islām often lapse into a false dichotomy of Orientalist/Fundamentalist tropes. A popular reimagining of Islām is desperately needed and anarchist political philosophical traditions offer the most towards this pursuit. By constructing a decolonial and abolitionist, non-authoritarian and non-capitalist Islāmic anarchism, Islam and Anarchism philosophically and theologically challenges authoritarian and capitalist inequalities in the entwined imperial context of so-called post-colonial societies like Egypt, and settler-colonial societies (the U.S./Canada) that never underwent decolonization and are symbolically, historically, and materially interrelated.

Political theology amidst and against human caging must carry out continued rigorous analysis of the practices that support this system. It must continue to critique the social power wielded against liberation by American Christians historically, and contemporarily as well by non-Christian religionists and seculars who have accepted the terms implicit in the contract with whiteness.

Combinations of theology and anthropology have been criticized for losing track of what theology ought to be about. Yet this loss might be precisely what enables scholars to understand political practices which point towards that which escapes both the theological and the anthropological grasp—a pointer which could be crucial to fashion solidarities that connect faiths in the pursuit of justice.