Pentecostals’ political commitments reflect processes of memory and amnesia, assimilation and identity… the stronger the memory of sojourning, migration and exile, the healthier the entrails of compassion for the soujourner’s wellbeing; the greater the distance from the memory of a wandering past, the greater the buy-in to a nationalistic Malthusian ideology that, among other things, paints the sojourner as law-breaking menace to the host society.

Almost a quarter of a century after that night in Pensacola, Trump supporters brought their shofars to a “Jericho March” at Washington D. C. in a manner resembling that decades-old revival meeting. Like the Brownsville attendees who cheered for Gideon’s victory, the Jericho March called to mind a biblical story of Joshua at Jericho, another conquest with the sound of a shofar.

Could prophetic politics, with its unique emphases, allow us to envision another, possibly less dogmatic and more differentiated form of political theology? Could focusing on the schism between prophetic voice and political institutions reveal a different understanding of political theological concepts, beyond the realm of power and sovereignty?

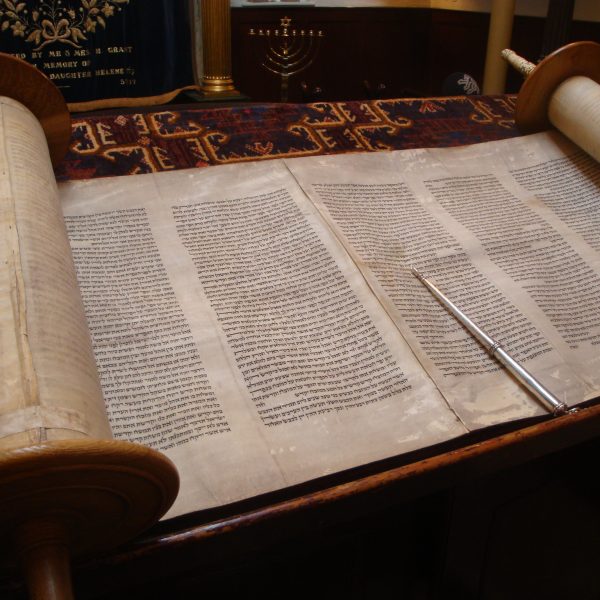

Rather than understanding political theology as a single school of thought, I seek to define political theology as a more inclusive category by looking at the rich historical resources within each of the Abrahamic religions that help each tradition unpack the complex relationship between the political and theological spheres

The rabbinic formation of the goy involved a whole project of Othering, whose medium and toolkit was provided by halakhic discourse, while its ideology was supplemented by the aggadic midrash, where goy is presented as a conduit for the presence of God in the human world and a sure trace for His steps in history.

The Jews is the great constant of this book, persisting from Old Testament to Tel Aviv, as an ahistorical collective, undisturbed by text and politics, what the book calls ethnos, goy. This book’s apriori is the Jews as a goy.