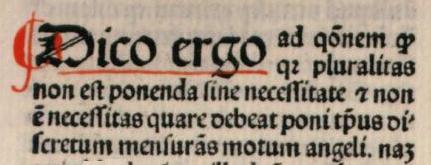

…there is another way in which human judgment often aspires to God-likeness: when it seeks to control the future course of events, preventing future evils, rather than merely rectifying existing wrongs.

Of course, there is a plausibility in this aspiration, since prudence is one of the essential political virtues, and prudence is above all concerned with weighing future consequences, with planning and forethought, with mitigating foreseen harms and maximizing prospective benefits. But prudence, in the scheme of cardinal virtues, must remain always the handmaiden of justice.

The Right of the Protestant Left: God’s Totalitarianism (Palgrave Macmillan, 2012) is really three books rolled into one, with three separate but overlapping arguments. Because of this, it can be hard to follow the different strands. I thought the most helpful way to introduce my book to readers would be to unpack each of the arguments. Before I begin, though, let me define briefly my subjects, the “old ecumenical Protestant left.” Like the old left it was affiliated with, the old Protestant left has often been reduced to a few of its leaders, namely Reinhold Niebuhr and Paul Tillich; the community orientation of the movement has thereby been lost…