The law is a dying and rising reality, not a dead letter etched in stone. Through the hermeneutics of resurrection words once consigned to the grave of the past burst with liberating and life-giving force upon an unsuspecting world.

The promise of the new covenant in Jeremiah 31:31-34 contains political dimensions that typically pass unrecognized, but which provide a rich description of an ideal polity. This prophetic vision can serve as a powerful counterpart and companion to more conventional political utopias and idealized societies.

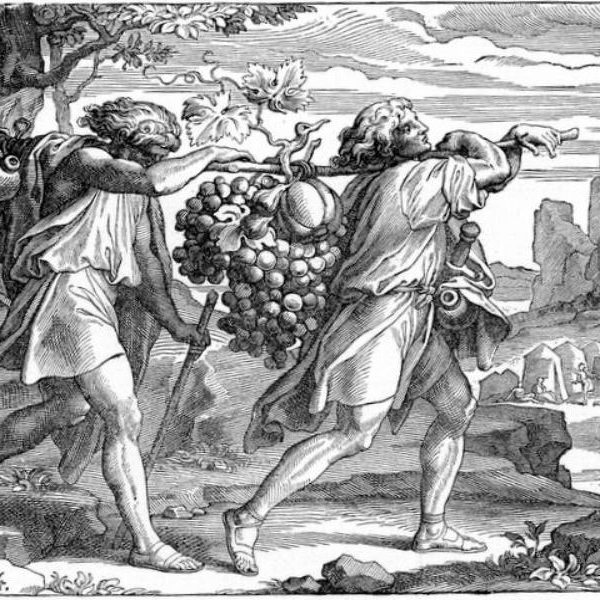

Exodus reminds us of what as human beings we have in common with the land and all of its resources—we are all both creations and possessions of the eternal God. In light of this, as we recognize and respond to our own needs and desires, making claims on the land as a result, we must also recognize the land as possessing its own distinct claims, dignity, and integrity.

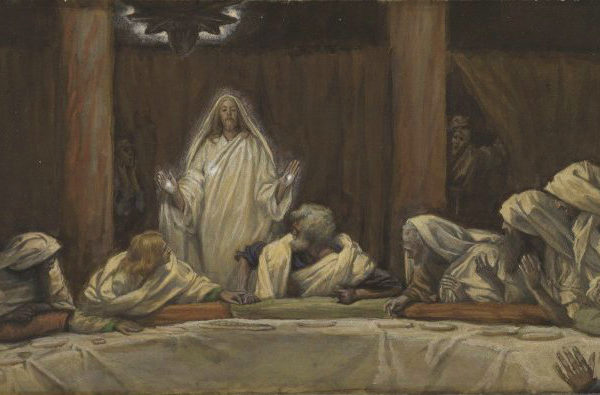

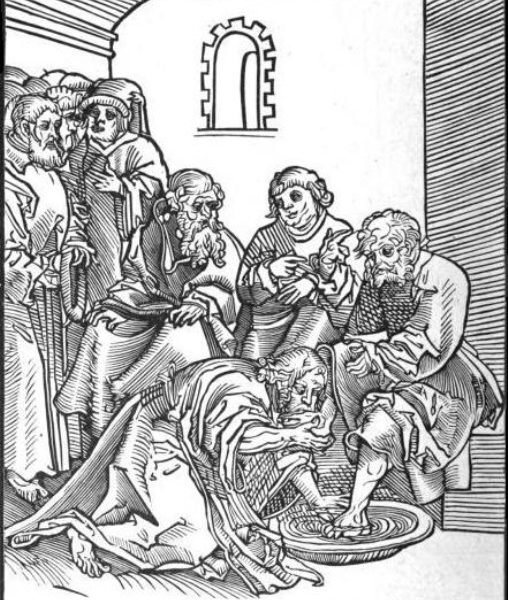

Christ’s actions on Maundy Thursday present a challenge to Enlightenment views of property. Through the Eucharistic vision of Christianity, we become more like Christ, and we do so together enveloped in an all-encompassing commandment of love: we grow together, not only in that we all simultaneously grow, but the barriers between us dissolve and our original love is mended.

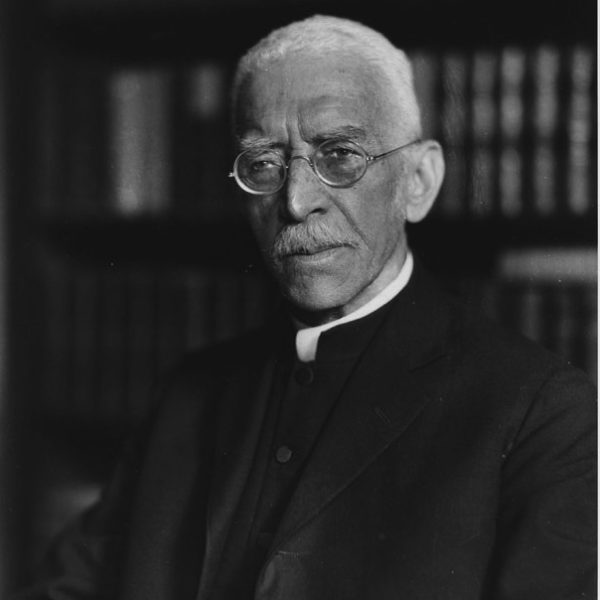

““I cannot believe that the men who occupy the pulpits of this land, assuming that they are men of ordinary intelligence and common sense and that they have, as they ought to have as leaders, some little knowledge, at least, of the Word of God, are without some convictions on the subject (of race prejudice), that they do not know that it is wrong, contrary to every principle of Christianity.”

Personally, I’m glad that Hosea is in the lectionary, though there is not much in it that we will “like.” As it is with spinach and colonoscopies, we can nonetheless grasp the value of things which otherwise might leave us cold.