Now that the election season is over in America, it might be a good time to take a step back and take a longer, more substantive look at some of the principles of Christian social thought than is sometimes possible in the midst of soundbites and stump speeches. Given the religious makeup of the candidates at the top of the tickets, Catholic Social Teaching (CST) was the focus of some attention in the national political conversation. It’s been noted that the political overlays onto religious faith are often just as constricting and reductive as partisanship itself. As Robert Joustra has observed, “Isn’t it ironic that the ecclesial conversation is essentially a thinly-baptized version of exactly the same disagreements in the secular world, but with less technical capacity and more theological abstraction?”

This is in some sense what has happened to principles of CST like subsidiarity and solidarity.

In the 17th century, although the evangelical theme of the two kingdoms is everywhere. It is often somewhat hidden, though operant, behind other more forefront matters of contest–self-interest vs sociality as the basis of society, the divine or human grounds of legitimate rule, the relation of the State to nascent civil society, public and private–and sometimes the thing itself goes under aliases. It sometimes plays a greater role in the thought of the doctrinally idiosyncratic, for instance Hobbes, than it does in that of those otherwise more orthodox, such as Richard Baxter. This is a very vast and complicated field. Given that this is to be such a short overview, we will consider here merely one aspect of Lutheran two-kingdoms doctrine, that of the denial of political power to the clergy, and point to a few landmark instances…

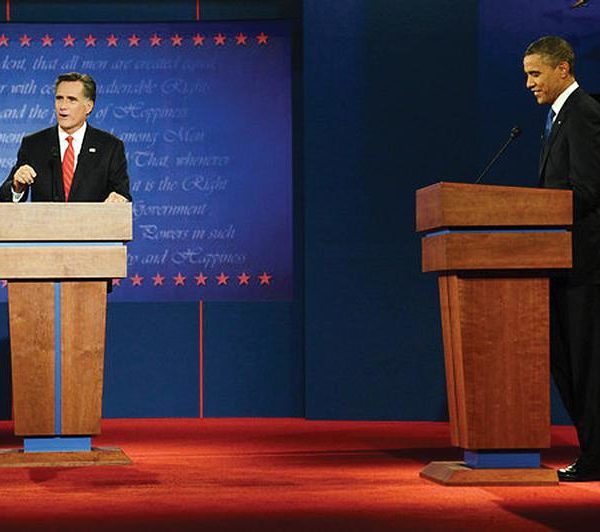

In the first presidential debate of 2012, Barack Obama and Mitt Romney tried to outdo one another in currying favor with the middle class. Yet Catholic social teaching proposes a preferential option for the poor. Catholics are called to promote the common good of all by putting the poor front and center.

Some challenges and opportunities are the same on either side of the pond for those of us teaching political theology. Those teaching in seminaries and other ‘confessional’ contexts will find the same resistance to ‘politicizing’ faith from conservative students and the same blasé assumptions from liberal students who obviously already have this all sorted because they are good liberals, both theologically and politically (more on these challenges in Part 3, next month). Those teaching in liberal arts universities will share similar struggles with how (or if) the discipline can be normative or formative in these contexts. And we will all share the wonderful opportunities involved in drawing students beyond their inherited binary views of the theological and the political. In other ways, the challenges and opportunities differ considerably on either side of the pond….

It’s no secret that many bishops, including Cardinal Timothy Dolan of New York, are incensed with the Obama administration over contraception coverage requirements under the Affordable Care Act. Bishops have missed few opportunities to blast the presidentas hostile to religious liberty – a meme that Mitt Romney has eagerly picked up on in a campaign ad that depicts President Obama as waging a “war on religion.”

But the selection of Rep. Paul Ryan – an intellectual darling of the conservative movement who embraces Catholic teaching to defend his policies – has complicated the Catholic narrative during these final months heading into the election….

For years now, one of Giorgio Agamben’s major concerns has been the fracture that lies at the heart of modern humanity (i.e. humanity’s sense of sovereignty). This is something he has described in a variety of contexts as that which divides the experience of something from one’s knowledge of it (cf. his Infancy and History). Due to such a fracture, we are no longer able to experience life as we ought to. The task of poetry (as it deals with our experiences) is subsequently forever divided from that of philosophy (that which deals with our knowledge). Such divisions, I would add, have since become the preeminent focus of Agamben’s work, taking him on a quest against all forms of representation that would sever the ‘thing itself’ from its image. These thoughts, moreover, have taken him toward an inspection of similar divisions said to lie at the base of our perceptions of the divine (i.e. God’s sovereignty). […]

The Kingdom and the Glory: For a Theological Genealogy of Economy and Government, which continues Agamben’s interest in the history of sovereignty and the exception, brings the discourse of theology to the forefront of questions about the nature of modern political economy and government. Agamben’s claim is that theology has left its indelible signature on and therefore deeply animates modern life. But how? […]

Religious truth is like troth, the experience of fidelity where one is affianced and then betrothed. What is true, then, is an experience of faith, and this is as true for agnostics and atheists as it is for theists. Those who cannot believe still require religious truth and a framework of ritual in which they can believe. At the core of Wilde’s remark is the seemingly contradictory idea of the faith of the faithless and the belief of unbelievers, a faith which does not give up on the idea of truth, but transfigures its meaning.

As the Iowa Caucus approaches, increased attention is being paid to the religious affiliations of the candidates for the Republican presidential nomination. Much of this discussion has centered upon Mitt Romney’s Mormonism, but the media has also paid a significant amount of attention to Newt Gingrich’s Catholicism. The latest round of controversy in the mainstream media began with Laurie Goodstein’s New York Times piece, in which she speculated about whether Gingrich’s 2009 conversion to Catholicism fits into a broader shift towards the right for Catholic participation in American politics in the post-Kennedy era. Likewise, Barbara Bradley Hagerty’s NPR piece narrated the details of his conversion process, highlighting the pivotal role of his current wife, Callista, as well as his attraction to the intellectual tradition of the Church.

“Political theology” as discourse came back into circulation almost a hundred years ago thanks to the efforts of Carl Schmitt. In Germany, at least, its feasibility as a theological category was promptly booted out of play by his close friend Erik Peterson (d. 1960) in an oft-cited – but less often read – monograph on “Monotheism as a Political Problem” (1935). That and other writings of Peterson’s are now available in English translation, most of them for the first time, in my edition of Theological Tractates (Stanford University Press, 2011). Peterson reveals himself to have been an “anti-political” theologian who yet possessed an acute sense of the political dimension of subjects as diverse as liturgy, mysticism, ecclesiology, and martyrdom.