Language and meaning originate not from a fullness trying to communicate itself but from a lack that strives after enjoyment.

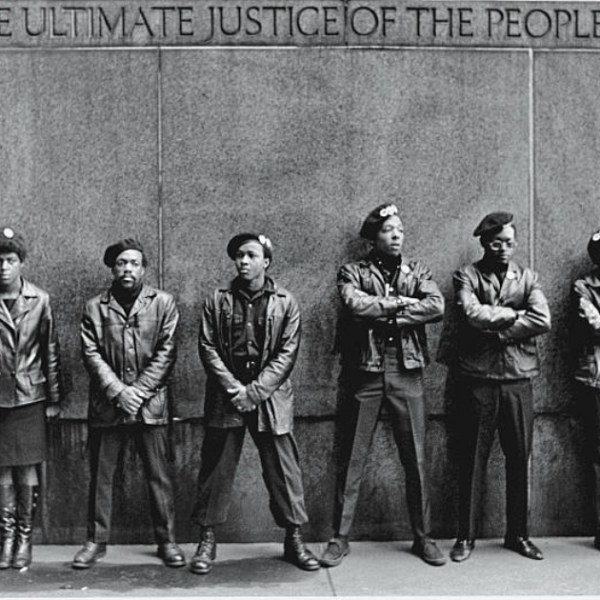

Situated on this eschatological middle ground, political theology must reckon with how we live in a time when the kingdom of God is present, creating moments of transformation and rupture…To speak truthfully, political theology must also speak to the quotidian joys and everyday struggles that make up the ordinary time of our lives.

How can community be grounded, if neither in force nor in love? To find out, we must reckon with Arendt’s reading of Augustine, for whom love and force were intimately intertwined.

William Desmond (Institute of Philosophy, KU-Leuven, and Department of Philosophy, Villanova University) introduces the latest issue of Political Theology (guest-edited by Péter Losonczi), which is devoted to the theme, “Evil and Political Theology.” His lengthy introductory essay appears here in two parts, first introducing the theme in general, and tomorrow introducing some of the particular contributions.

…Instead of treating contemporary consumerism as a wholly negative phenomenon, Augustine suggests we look at the issue differently. The behaviour of the shopper or spiritual tourist is the way it is because of the deep structure of the human condition. The longing for fulfilment is at root an existential need: a secularized version of the call at the heart of Augustine’s Confessions: ‘You have made us for yourself, O Lord, and our hearts are restless until they rest in you.’

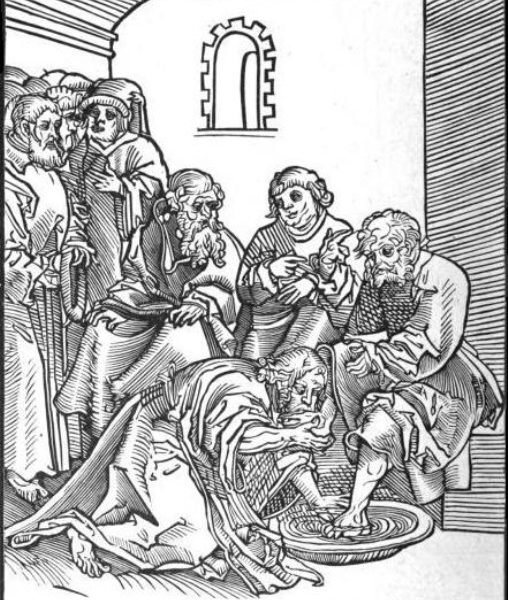

Christ’s actions on Maundy Thursday present a challenge to Enlightenment views of property. Through the Eucharistic vision of Christianity, we become more like Christ, and we do so together enveloped in an all-encompassing commandment of love: we grow together, not only in that we all simultaneously grow, but the barriers between us dissolve and our original love is mended.