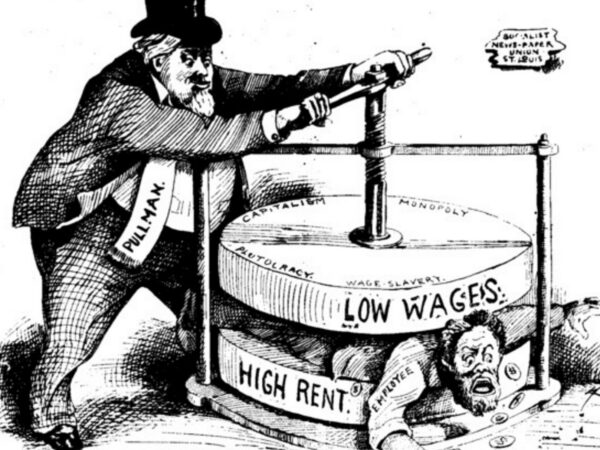

While some white American converts to Pentecostalism in the early 1900s were experiencing a resurgence of Jeffersonian populism of that era, Mexican nationals were living through revolutionary upheaval of their own. And like the older populism of American evangelical lines, the Mexican revolution’s radical populism was also agrarian, influenced by Jacobinism, and hostile to establishment elites.

We see this wholesale adoption of White Evangelical practices in the Latino/a Evangelicals’ increasing support of the White nationalist philosophy which undergirds the White Evangelical theological position. The 2016 presidential election, Trump’s subsequent term in office, and the 2020 presidential election have made this all much more publicly clear.

Regardless of our interrogation of it, the terminology of “religion” is operative in the world—not only among the scholars who frame it as a second-order category, but among our interlocutors and kinship networks. Given the baggage that often accompanies it, perhaps it is unsurprising that so many of us are hesitant to apply this label to the people, places, and practices to which we attach meaning.

When we read of God enthroned as the great king, perhaps we can imagine a system of governance where our political rivals are not beaten into submission, but are disarmed by love; where those who are different from us are respected, listened to, learned from; where brute force is neutralized by a refusal to retaliate and is resisted through active non-violence. Toward this end, God is indeed the great leader, the one who models “power under” for all of us.

Born out of the recognition that the place of guns in the United States cannot be adequately explained via statistical data—that qualitative accounts are urgently needed—these approaches aim to understand the logics of self-defense and self-preservation at play in forms of life in which guns have been incorporated.