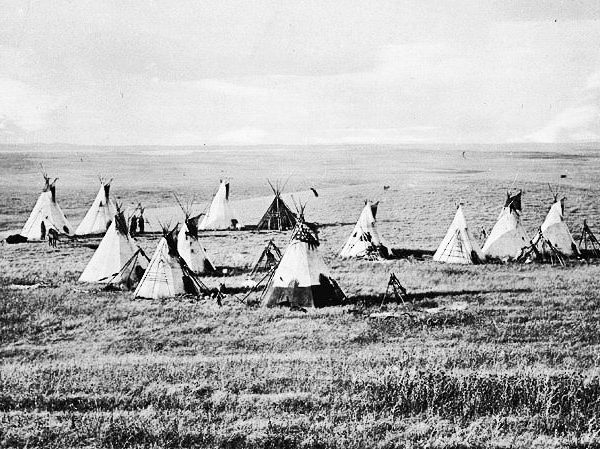

It is not always possible (or advisable) to separate the “political” from the “religious” or “cultural” in Indigenous contexts. Indeed, all of these are concepts developed by outsiders to describe Indigenous life. Instead, Indigeneity invites scholars of political theology and related fields to consider the relationships between these threads of cultural life.

Food sovereignty represents a refusal of a globally commodified food system in favor of systems and institutions that support self-sufficient communities.

By spiritualizing place, and thereby transmogrifying place-based identities into racialized ones, Christianity cooperated with the machinations of settler-colonial capitalism in its world-making project. Thus, returning to a consideration of land as one location of God’s action is basic work for any political theology that aspires to move in a decolonial direction.

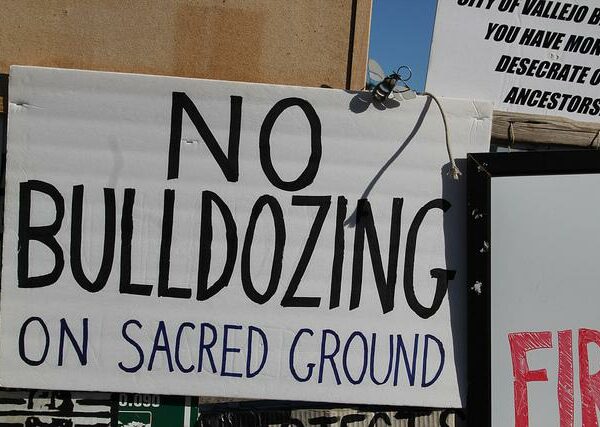

Jesus’ story of the Rich Man and Lazarus is a challenging account of the one neglected at the gate, who ends up being exalted, while the one at ease within is cast out. This story has a particular contemporary resonance in the context of the recent events surrounding the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline.

Exodus reminds us of what as human beings we have in common with the land and all of its resources—we are all both creations and possessions of the eternal God. In light of this, as we recognize and respond to our own needs and desires, making claims on the land as a result, we must also recognize the land as possessing its own distinct claims, dignity, and integrity.

What political theologies are embedded in and shape Zionist and Palestinian refugee mappings of space and place? This is the animating question of my new book, Mapping Exile and Return, which stems from my doctoral studies in theology at the University of Chicago and 11 years of work in the Middle East.