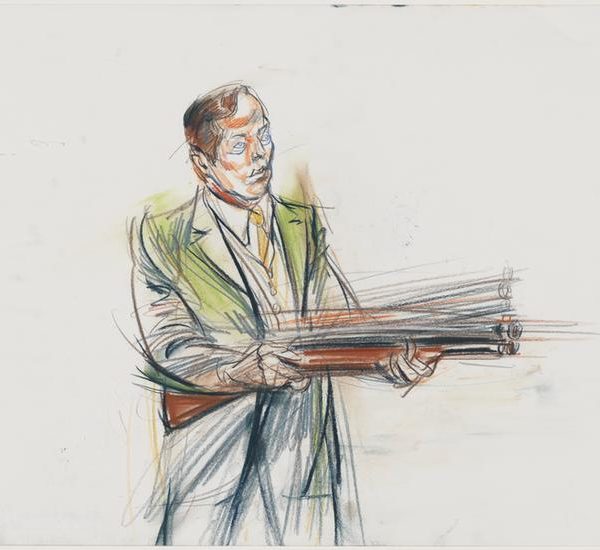

Three years before, Eleanor Bumpurs had been shot. A sixty-six year old black woman shot by a white police officer. Shot twice. With a shotgun. In her home. A case against the police officer wound through the courts in fits and starts. In 1987 the officer was acquitted. It was then, on the streets in front of the courthouse, that the press recorded for the first time the chant, “no justice, no peace.”

The myth of Captain America introduces us to a serious quandary. Can liberal democracy be de-coupled from violence or is it doomed to repeat old battles? For Christians the question is doubtless a complex one. The Church can doubtless find much in Rogers’s democratic creed to admire; his sense of self-sacrifice, his public spirit and sense of civic duty. There is something of the righteous pagan in the Captain America myth which should not be lightly dismissed.

This is the fourth, and final, post in a series that was kick-started last September with a short discussion of how the growing field of just intelligence theory might be overly influenced by jus contra bellum thinking, or what Tobias Winright has coined “the presumption against harm version of just war theory.” This particular variant of just war theory is defined at its core by a presumption against war or a presumption against the use of force.

In light of the two kingdoms doctrine and the separation of church and state, understanding the appropriate form of Christian prayer for and engagement with the political realities of our societies can be complex. In Jeremiah’s message to an exiled people, we find a pattern for prayer in a pluralistic context, a calling that identifies our primary task to be one of seeking the common good and welfare of our communities, rather than one of submission or conversion.

I am grateful to Bill Cavanaugh for taking the time to respond to my blog post of two weeks ago, “Modernity Criticism and the Question of Violence,” and giving me the opportunity to clarify better the nature of my criticisms. Clearly such clarification is in order, as Cavanaugh’s response seems to have struck off in something of the wrong direction, defending theses that were not really under challenge. If I may adapt the opening from his post, Cavanaugh’s response would raise significant difficulties for the thesis of my critique if (1) the argument of that critique were directed against The Myth of Religious Violence and (2) my purpose was to endorse Steven Pinker’s triumphalist progressivism. The first of these premises is false, and the second is highly questionable.

Brad Littlejohn’s blog entry here last week would raise significant difficulties for the thesis of my book The Myth of Religious Violence if 1) the argument of that book is that modernity is more violent than previous epochs and 2) Steven Pinker has proven that modernity is in fact less violent than previous epochs. However, the first of these premises is false, and the second is highly questionable.

Debates over the virtue or vice of modern liberal political arrangements often boil down to narratives about violence, whether we are speaking of violence in its literal sense, or in the more metaphorical use made so fashionable by postmodernism, namely, the attempt to erase or neutralize difference. According to the eulogists of liberalism, it rescued us from the darker ages of religious tyranny, in which zealots of orthodoxy used political power to enforce uniformity, and even to violently persecute dissenters.