Pentecostals’ political commitments reflect processes of memory and amnesia, assimilation and identity… the stronger the memory of sojourning, migration and exile, the healthier the entrails of compassion for the soujourner’s wellbeing; the greater the distance from the memory of a wandering past, the greater the buy-in to a nationalistic Malthusian ideology that, among other things, paints the sojourner as law-breaking menace to the host society.

Almost a quarter of a century after that night in Pensacola, Trump supporters brought their shofars to a “Jericho March” at Washington D. C. in a manner resembling that decades-old revival meeting. Like the Brownsville attendees who cheered for Gideon’s victory, the Jericho March called to mind a biblical story of Joshua at Jericho, another conquest with the sound of a shofar.

But how could Trump seduce a great majority of the Jesus-believing, Bible-thumping, church-attending evangelical conservative community when his values are so contrary to those of Jesus, the Bible and what the church should stand for?

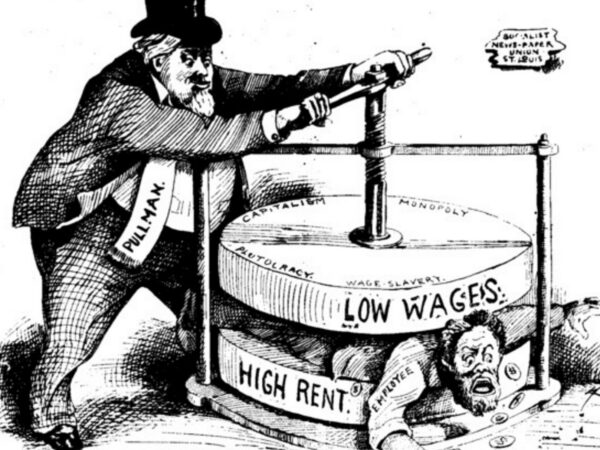

While some white American converts to Pentecostalism in the early 1900s were experiencing a resurgence of Jeffersonian populism of that era, Mexican nationals were living through revolutionary upheaval of their own. And like the older populism of American evangelical lines, the Mexican revolution’s radical populism was also agrarian, influenced by Jacobinism, and hostile to establishment elites.

We see this wholesale adoption of White Evangelical practices in the Latino/a Evangelicals’ increasing support of the White nationalist philosophy which undergirds the White Evangelical theological position. The 2016 presidential election, Trump’s subsequent term in office, and the 2020 presidential election have made this all much more publicly clear.