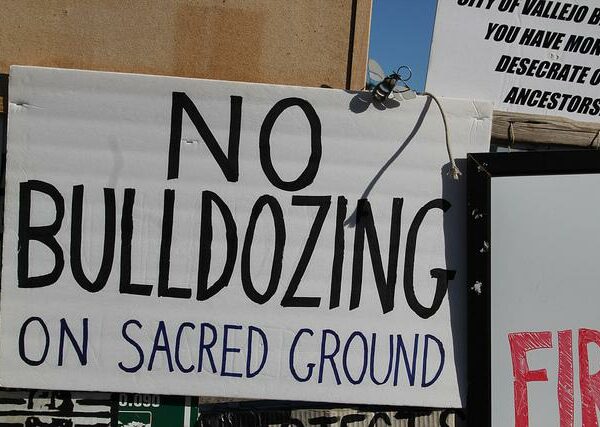

By spiritualizing place, and thereby transmogrifying place-based identities into racialized ones, Christianity cooperated with the machinations of settler-colonial capitalism in its world-making project. Thus, returning to a consideration of land as one location of God’s action is basic work for any political theology that aspires to move in a decolonial direction.

We are shocked. Morally outraged. How could a US president tout “law and order” to incite a blatant attack on “American democracy” and “the rule of law,” encouraging his supporters to storm the US capitol? Commentators decry such hypocrisy, stating the obvious contradiction between US constitutional law and violent coups. My contention in this essay is that no such contradiction exists.

Church-state relations have been examined as a catalyst of legal conflicts, particularly in the United States today. Yet what do we mean when we talk about the “church” in legal contexts?

A second expression of relationality is covenant. It is a bond between distinct parties where each gives for the flourishing of the other. Unlike contract, which protects interests, covenant protects relationship.

Rendering to God what was God’s meant offering our lives as living sacrifices of worship to God, as one would offer coins as tax and tribute to one’s sovereign. The human was theologically monetized—or coined—in the name of dedication to God.

Indigenizing philosophy through the land then is more than a culturally distinct way of philosophizing… it is a process of decolonization in the form of a revitalization of the relational modes of Indigenous life grounded in land as the relational ground of kinship and human beings as grounded in and inextricably entwined with this relational kinship ground.