Humans have grown exponentially in our propensity and power to conquer the earth itself. Despite being newcomers relative to neighboring species, humans usually behave as if we owned the place. But Psalm 95 speaks clearly: When we come into God’s presence—and there is no place God is more vividly present to us than in creation’s midst—the psalm says to come with thanksgiving, the polar opposite of greed.

In the book of Genesis, after the changing of Jacob’s name to Israel, no one calls him by his new name. Instead, the name “Israel” seems to exist as his “true name” and Jacob as his “use name.” “Jacob” is the name that everyone calls him, but he knows that “Israel” is who he really is inside. God has named him “Israel,” and consequently, this will become his legacy.

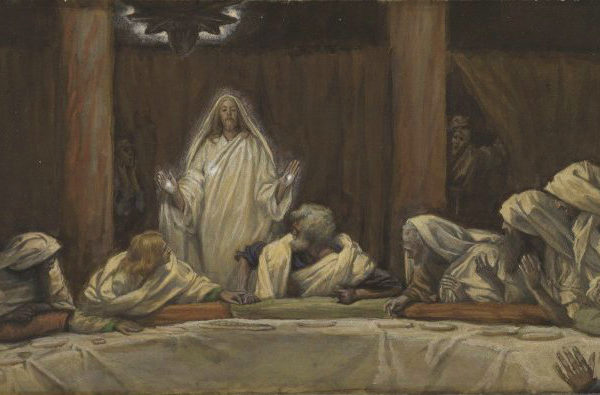

That the resurrection is a beleaguered doctrine in North America and in Europe is hardly a new revelation. For all its technological wonders, modernity is uncomfortable with old-fashioned miracles. Pre-modern ways of talking about Jesus’ resurrection don’t translate easily for an audience that demands scientific corroboration and empirical evidence. As a result, Christianity has chastened and tamed this story in a number of ways.

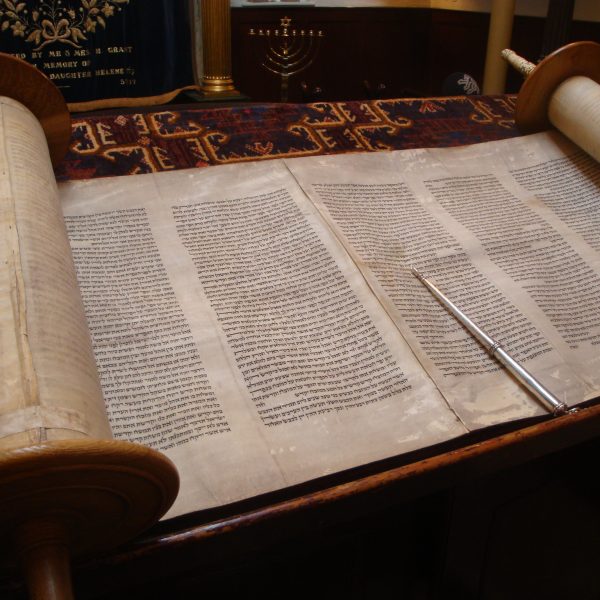

The rabbinic formation of the goy involved a whole project of Othering, whose medium and toolkit was provided by halakhic discourse, while its ideology was supplemented by the aggadic midrash, where goy is presented as a conduit for the presence of God in the human world and a sure trace for His steps in history.

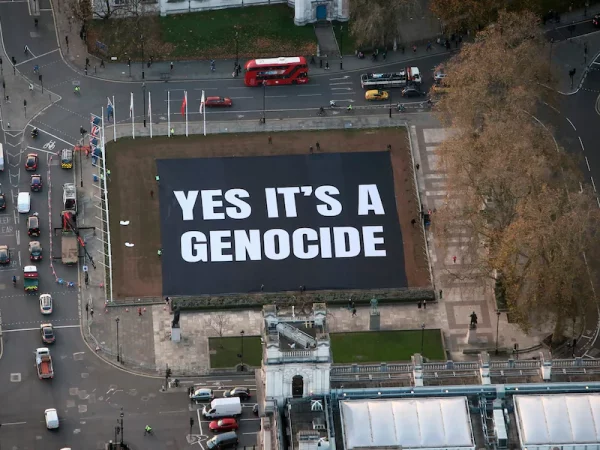

The Western inability to recognize Palestinians as fully human is often attributed to Islamophobia, framed as a post-9/11 construct that portrays Muslim violence as a threat to the liberal West. However, this perspective remains superficial. To truly understand the roots of Western hatred, we must look deeper—beyond contemporary narratives—into the ideological foundations of Western thought.

The law is a dying and rising reality, not a dead letter etched in stone. Through the hermeneutics of resurrection words once consigned to the grave of the past burst with liberating and life-giving force upon an unsuspecting world.

What is theology for? In her new book, Karen Kilby outlines the purpose, as well as the limits of theological reason.