Last month’s presidential election was characterized by unprecedented rancor and bitterness. With the election over and Obama still in office, the partisan posturing has shifted to the “fiscal cliff” debate and the prognosis that huge spending cuts and an increase in taxes could send the American economy into a tailspin. The issue seems to have changed, but the political climate has not. Even worse than the puerile behavior of elected officials is the level of acrimony displayed by American citizens toward those who disagree with their political affiliation…

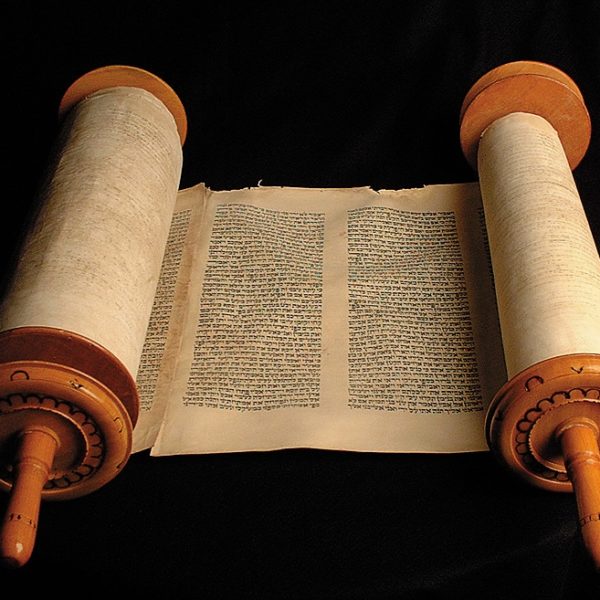

It is a challenge to reflect on politics and advent together. As advent emerges and we begin to anticipate the emergence of God’s presence into the world anew, as we expect the child who taught peace and preached liberation for the poor and oppressed, I cast my eyes on the political landscape and struggle to glimpse what might be breaking forth with new life. Perhaps this is a problem with how we conceptualize the birth of Jesus, as a grand cosmic event, an episode of a preordained salvation history, the inauguration of a new kingdom of peace on earth. There is another element to this extraordinary story, its ordinariness. Jesus is born in a Galilean backwater, to an unwed teen mother, lost in a crowd of travelers. Jeremiah prophesied to his ancient community about a time when justice and righteousness will emerge into history. We still await the fulfillment of this prophesy. But refracting this vision through the circumstances of Jesus’ birth will perhaps teach us to look for this hope in unexpected places…

This teaching marks a turn to family ethics. The Pharisaic question about divorce again serves as a foundation upon which Jesus makes a larger teaching that transcends the context of their specific query to make a larger points. In this case, Jesus outlines an expansive family ethic rooted in an understanding that, with the family at the center of social life, intrafamilial ethics have vast political consequences. In discussing both marriage and children, Jesus imagines models of the family that are radically expansive relative to his context…

John’s gospel is replete with splendid imagery of the saving power of Jesus, so much so that it can be easy to wonder how the disciples could have even considered turning away from Jesus, even at the cross. But here we are, still a far cry from the cross and Jerusalem, long before the last supper and the cock’s crow, and rather than the masses that we’ve grown to expect to see coming out towards Jesus in droves, we are told that many who were following him turn away from Jesus en masse. How could this happen? What motivates those who leave? And what’s more, in the face of such harsh words–of inevitable tribulation ahead–what motivates those who stay? These are the politics of today’s gospel text…

Nolan’s Dark Knight trilogy is obsessed with the question: what are the conditions of possibility for political judgment? Judgment, as Oliver O’Donovan has written in The Ways of Judgment, “both pronounces retrospectively on, and clears space prospectively for, actions that are performed within a community” and is therefore “subject to criteria of truth, on the one hand, and to criteria of effectiveness on the other” (9). Although judgment must meet both criteria, very often in the world of politics, they appear to be in rivalry. Truth-telling, in a world of fickle voters and predatory media, in a world of terrorists and hidden threats, can seem like a very unwise proposition, a luxury that must be dispensed with if order and justice are to be preserved. This tension haunts Nolan’s trilogy.

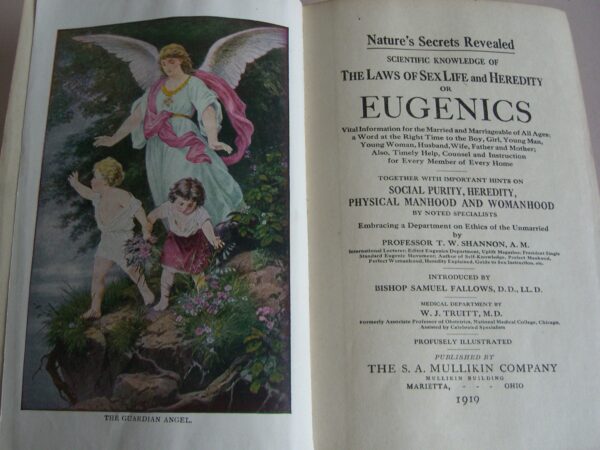

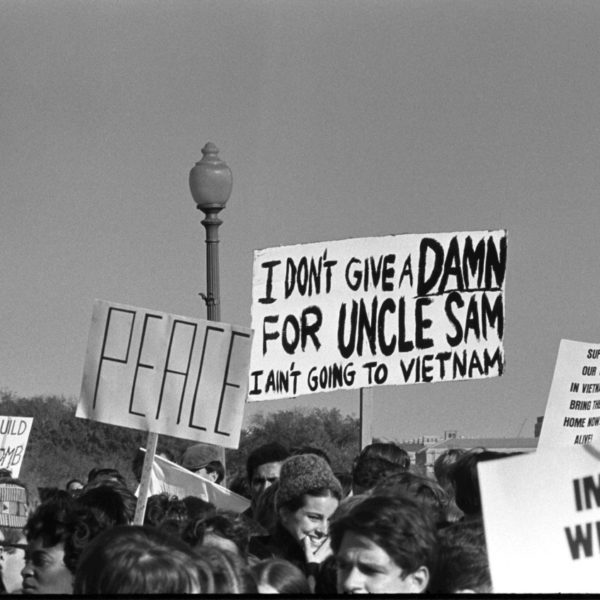

The pursuit of truth and justice is often onerous and taxing. The incremental gains accomplished by strikes and protests, grassroots organizing, and community coalitions pale in comparison to the large-scale success achieved by corporations and the governmental institutions who collude with each other. The quest to halt imperialistic conquests by the American war machine, ameliorate poverty, reform a racist and unjust judicial system, and empower communities can often seem like a dead end street, but the light of hope still shines through the darkness […..]