The Weimar Moment: Liberalism, Political Theology, and Law, edited by Leonard V. Kaplan and Rudy Koshar, is a set of papers from a conference held at UW-Madison in the fall of 2008 (Lexington Books, 2012). Many of the papers will be of direct interest to readers, most notably perhaps the set dealing with Karl Barth. Here I want to point out some of the more important observations and analyses that surfaced during the discussions (full disclosure: I attended and have a paper in the proceedings).

Given the important role played by American Catholics in determining the outcome of presidential elections, many commentators have speculated that Newt Gingrich might be the one to capture the prized Catholic vote.

For Gingrich’s campaign, his recent conversion from Southern Baptist to Roman Catholicism almost functions like the makeovers of popular reality TV shows. His past record of “double spousal abandonment” and congressional ethics violations, we are told, are sins of a previous life that are irrelevant for the newly made-over “Catholic Newt.”

In my prior posting, I was concerned with elaborating the disciplinary position from which I take up the project of political theology. It is a part of the secular study of our political practices and beliefs. Accepting these limits, I placed myself within the same modernist tradition as liberal political theory.

There is a deeper point to be made about the symmetry between theory and practice in the modern age. Liberal political theory is committed to the idea that an adequate account must be one that is fully transparent to reason. Theory is to be built through discrete, rational steps from common premises that purport to be universal. Accordingly, it is hostile to any privileged claims made on the basis of a particular faith, including claims for the existence of God or a natural order. In a parallel fashion, the modern, political order is to be autochthonous. It is to rest on nothing outside of itself. This is not a claim about history, which knows no beginnings; rather, it describes a secular understanding of the origin and ground of the state. This is an important idea, for example, in the decolonization movement: a post-colonial state can create itself through an original founding act. It need not express a pre-existing national or ethnic identity.

The Republic of Grace means to offer an extended account of why and how we, Christians and non-Christians alike, must learn to understand ourselves as continually, graciously, coming to be re-habituated, and recalibrated, into the grammar and language of love, even–and perhaps ultimately–in the public realm.

Translating Senghor’s political writings shows the continued relevance of Negritude in the conceptualization of political community in the wake of the encounter between Africa and Euro-America. However, framing the translation, like engaging any of Senghor’s work, ought to pay close attention to his African critics.

Tuning in to active nonviolence as a center of gravity in Jesus’ way, we can sense nonviolence as integral to the mission of the Catholic Church. This enables us to have a broader imagination of nonviolent praxis, a sturdier identity as interconnected beings, and an engrained commitment to better persist in active nonviolence even during difficult circumstances.

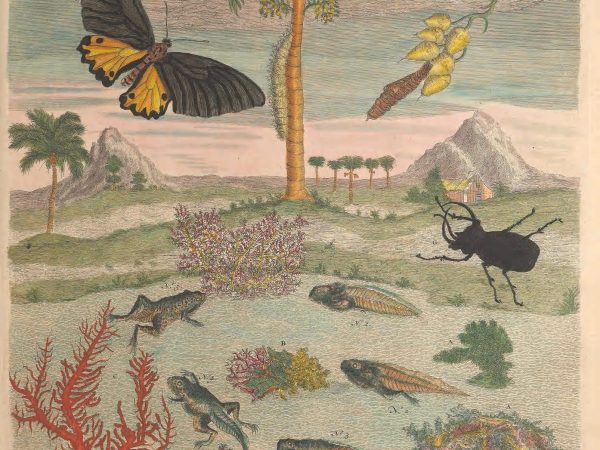

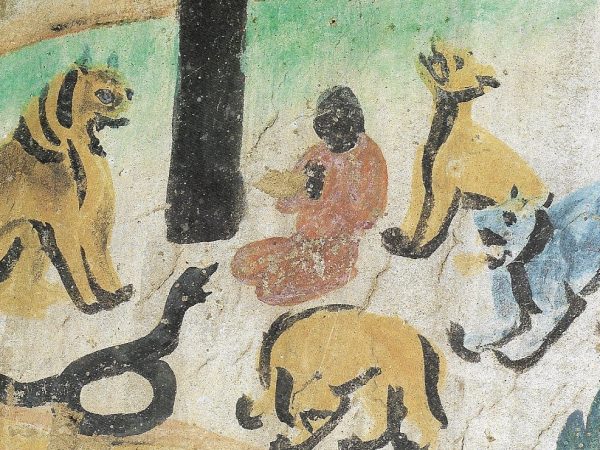

These books demonstrate that animal studies as a new field offers a powerful perspective for understanding the history shared with our companions in the multi-species universe.