Following this path, I intended to do a non-punitive reading on Cain’s wandering by presenting it as God’s opportunity to cultivate the land while moving around the territory. This view of the nomad seeks to rehabilitate another type of relationality with the Earth by recovering its dignity in different horizons.

In his book Senghor’s Eucharist, introduced here, David Tonghou Ngong focuses on Senghor’s poetry collection called Black Hosts as a starting point for understanding his political theology. He argues that Black Hosts is a Eucharistic theology that calls for the reclamation of the Eucharist for the remaking of the world.

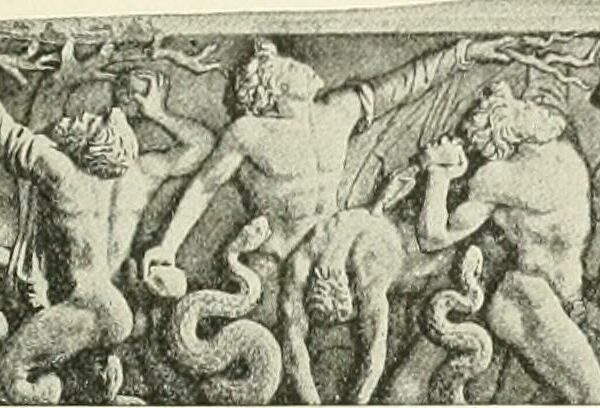

[S]ituating demonology more fully in its religious and theological contexts furnishes resources that not only nuance understandings of movements for whom demonization is central, but also recontextualize discussions of core political theological concepts, including sovereignty, power, economy, subjectivity, and freedom.

Refusal is a strong current resisting the structure of settler colonialism. It crashes, churns, and erodes the death-dealing dams of settler knowing. Its path turns away from the settler’s gaze.

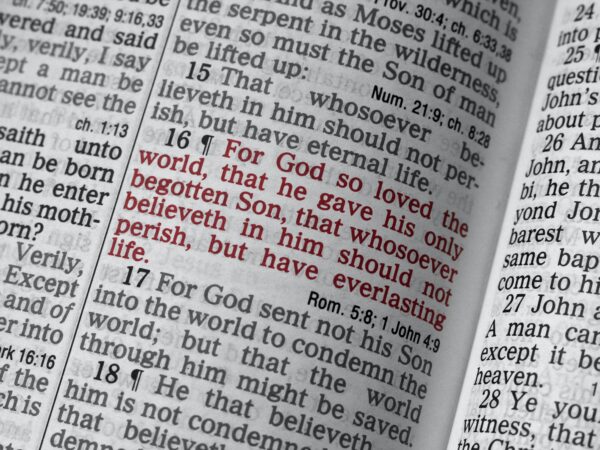

The God of Israel does not get so caught up in the national agenda that God neglects the prayers of individuals in pain. The best antidote to politics-as-usual is proper worship. Praising YHWH can keep our feet flat on the floor. As we worship the God who sees and the God who acts on behalf of the downtrodden, we seek to become like God. YHWH, rather than the human powers that be, becomes our model. In worship we become attentive to the things that God attends to, such as the grieving woman whose empty cradle signals an uncertain future.

Abolition is not just about closing prisons. It’s not just about stopping police or closing police departments, but it’s also about abolishing the police in our heads. It’s also about abolishing the prisons in our imaginations that prevent us from thinking about new ways and better ways to treat each other and to keep each other safe.