The Notre Dame Institute for Advanced Study hosted a conference at the beginning of this month on Theology and Black Politics. Opening with the question: “What is the Black Church?”, the conference addressed fundamental concerns regarding the nature of black politics and theology.

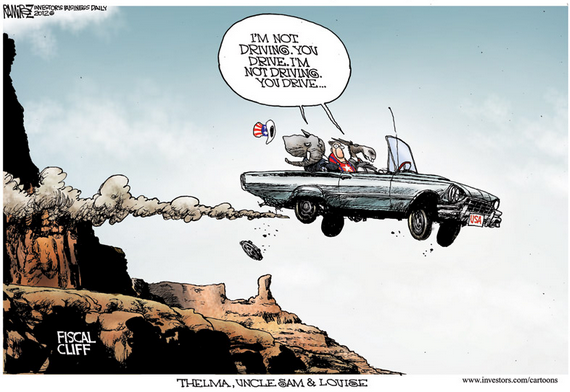

Four years ago, I was an idealistic college student who believed in change. Frustrated with the years of Bush-style imperialism and capitalism, I was ready for some big government and the return of civil liberties, singing the doxology Praise God From Whom all Blessings Flow as balloons reigned down and Obama waxed eloquent on a stage overlooking thousands of people. Needless to say, I have learned my lesson over the last four years. Although a less harmful sovereign, Obama turned out to be—surprise, surprise—a neo-liberal. The problem, however, was not with Obama, it was with me….

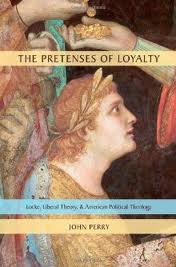

Chapters 4 and 5 of Pretenses of Loyalty constitute the heart of Perry’s argument, offering as they do an intriguing re-interpretation of Locke’s Letter Concerning Toleration and revealing the tensions that will bedevil it in following centuries. Perry’s overall thesis, we will recall, is that modern liberalism suffers from an amnesia, forgetting that there are in fact two prerequisites for a successful policy of religious toleration: harmonization of loyalties and abstract respect. Relying upon the latter alone, modern liberals find themselves flummoxed at the frequency with which border conflicts erupt between religion and politics—having agreed to tolerate all purely religious practices, governments find that many believers insist on expanding the scope of their religion to include civil matters. They ask that believers consent to be led behind a veil of ignorance, willing to treat others and themselves be treated as abstract rights-bearers, but many believers refuse.