Jean-Luc Marion waded into political discourse with his 2017 book Brève apologie pour un moment catholique (Brief Apology for a Catholic Moment) which uses aspects of his phenomenological and theological project to argue for a model of non-political politics: one based exclusively on the perfect will of the Triune God.

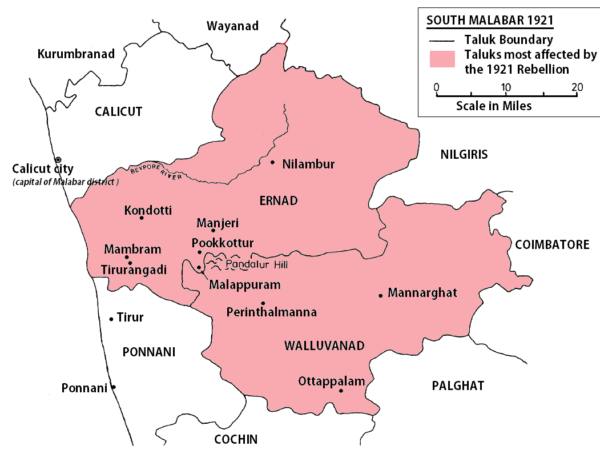

This blog post investigates and problematizes a certain narrative strategy in the historiography of Malabar rebellion, in which “war” (“yudham”) and “riot” (“lahala” or “mutiny”) were configured on the model of “politics” and “religion”. The post asks what kind of sovereign formation was imagined in such a narrative strategy and why it needs to be addressed.

God’s call is not to engage in politics of personal power or self-service, but engage in a politics of liberation, one that ends the idolatrous hold on power so many have.

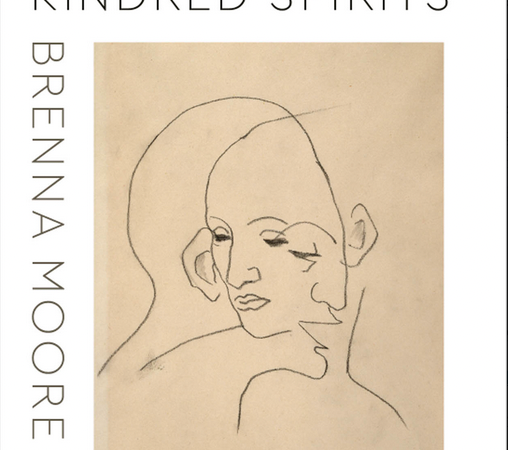

“Both authors travel to the margins and then send back a warning signal to fellow scholars about the limits and potential intrusiveness of our established methods.”

The judgment of history is a moral belief that, somehow in the long run, the good and the true will win out, since the “long arc of the universe bends towards justice.”

Joan Wallach Scott’s On the Judgment of History serves as an invitation to uncover a multiplicity of traditions, perspectives, and forms of agency that embrace discontinuity and tension while resisting closure, and the essays in this symposium function as an active experiment in precisely this type of endeavor.

For me, “political theology” thus names the study of the ways that imagination is embedded in sentient, desiring bodies, instantiated in vernacular forms of life and ordinary (ritualized) practices, and conjured in mytho-poetic metaphors, images or representations that are formalized by literary genres and assembled into scriptures.

![Political Awakening and Ascension of the Matuas in Post-independence Bengali Society (1947-2011) (স্বাধীনতা উত্তর পর্বে বঙ্গীয় সমাজে মতুয়াদের রাজনৈতিক জাগরণ এবং উত্তরণ [১৯৪৭-২০১১]), an interview with Kanu Halder](https://politicaltheology.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Haldar-1-e1666007172763-600x450.jpg)