If we understand political theology as the mobilization of theological ethos to manage political existence in the world, or theodicial redemption of being-in-the world of oppression and domination, the theology operational here could thus be tentatively called an anti-political theology. Anti-politics in the sense of the rejection of politics in favor of the immediacy of the oppositional freedom, and in its indifference in articulating sovereign futurities, which promise liberation in another worldly political order. In its fatal determination to rebel, it speaks only (or is only able to) of the irredeemability of this world.

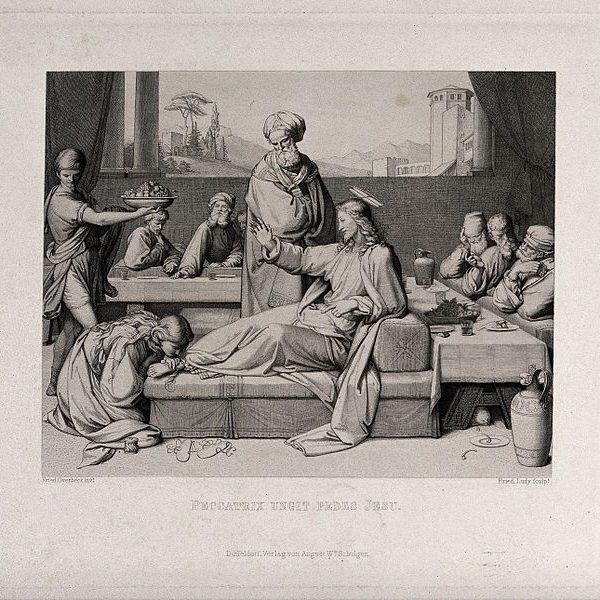

Contending against the dominion of sin and death requires the same wisdom and willing vulnerability that characterize Jesus. Exemplifying both of these characteristics means seeking a solidarity with the world’s plight while simultaneously refusing to assimilate to its norms of greed, selfishness, and domination.

Authoritarianism in Christianity is a feature, not a bug, and it is unlikely to change any time soon. Perhaps on its own it is a problem mainly to those inside the faith. But when Christian authoritarianism hooks up with fierce cultural reaction, it can become a profound problem for society.

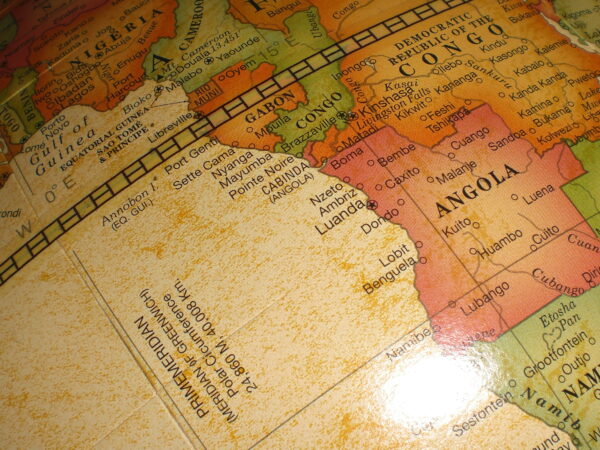

Contemporary African political theologies are a study in contrasts. A prophetic strand challenging unjust politics is alive and well, but so are political theologies that align with unscrupulous politicians and seek wealth at the expense of ordinary people. This dizzying situation raises questions of both substance and method about what African political theology is and how to do it.

It is as productive to think with as it is to think against Claude Lefort, a revolutionary-turned-philosopher who analyzed power and the political regimes to which it gives rise.